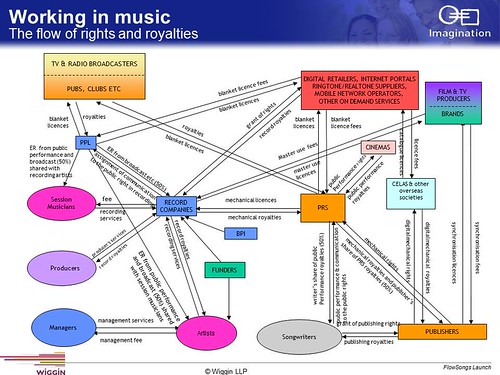

Earlier this month, this picture 1Note: the image is meant to illustrate the UK music industry, which is largely similar to the US industry but does have some differences. made the rounds online:

The response to this diagram was typically something like, “Look at how complex the music industry is!” – and nothing more. I suppose the conclusion to be drawn is that complexity, in and of itself, is bad.

But if you diagrammed any industry, you’d likely end up with a picture just as complex. How bout the food industry? You have your farms and raw material suppliers, processors and plants, grocery stores and restaurants, institutional food service providers, plus distributors, shipping providers, warehouses, etc. All industries have some degree of complexity to them, especially if you show each link in every chain. Most participants in an industry, however, do not have to concern themselves with keeping track of the larger picture; even in the graphic above, you’ll notice that most hubs have only one or two connections to other hubs.

The world is complex, and the idea that complexity by itself is bad is a silly one. There are problems which arise in complex systems, but scratching your head at a diagram of the system is not one of them. Clarity is certainly a goal for participants within an industry, but that does not mean that one unfamiliar with a particular industry can pick up a working understanding of the entire system by glancing at a diagram like the one above. Simple systems carry risks as well. We have antitrust laws to ensure that industries do not become controlled by too few participants.

Instead of leaving things at that, I thought we could take a closer look at some specific characteristics of the music industry that make it complex.

Double Your Pleasure

Copyrights form the foundation of the music industry. Copyright law itself is complex, and the music industry has the added bonus of dealing with not one, but two separate and independent copyrights. Songs (musical works) are protected by copyright, as are recordings of songs (sound recordings, or phonorecords). In my experience, understanding this distinction is one of the steepest parts of the music industry’s learning curve. Traditionally, songs are represented by notes and lyrics on paper. A sound recording incorporates a song but is independently protected by copyright itself, though that copyright doesn’t incorporate the copyright of the underlying song. So, think about the song “Twist and Shout” and how it was recorded by the Isley Brothers and the Beatles. In this example, there are three copyrights: the song, the Isley Brothers recording of it, and the Beatles recording of it. 2Hypothetically speaking. The reality may be different since US federal copyright law did not recognize sound recordings as copyrightable subject matter until 1972, though some states and the UK did before then. The owner of the copyright on a sound recording and the underlying song may or may not be the same. In the music industry, record labels generally own the copyrights to the sound recordings while music publishers generally own the copyrights to the songs.

Once you grasp the concept of the two copyrights involved, you’re faced with another twist. A copyright is not a single right, it is a set of several rights: the right to reproduce, distribute, and prepare derivative works (I’ll get to public performance rights in a moment). And wouldn’t you know, each one of these rights can be licensed, transferred, or sold individually. Not too bad? Let’s throw in the right to public performance. The copyright in musical works includes a right to public performance. The copyright in sound recordings does not; however, it does include a public performance right by digital audio transmission.

In other words, each track on a CD has two separate copyrights involved, with two slightly different sets of rights attached to each copyright. Now that we know that we are starting with an inherently complex foundation, let’s take a brief look at how additional complexity in the music industry has evolved.

Adapting to Changes

With the introduction of every new technology, Congress, courts, and the music industry struggled at times to figure out what role copyright law played. It’s important to keep in mind that the words used to describe the exclusive rights in copyright – “reproduce”, “distribute”, “public performance” – are legal terms of art. Their meanings do not necessarily follow logic, and one can’t necessarily deduce whether a particular use is a reproduction, a distribution, a public performance, or some combination by opening up a dictionary. Instead, the meanings of the terms evolve constantly through statute and common law, guided as much by practical considerations as by legal formalism. 3Nimmer on Copyright discusses this issue in its introduction: “An even more fundamental problem, with ramifications for both judge-made rules and legislation, is that words are often used in the copyright context with special meaning, at variance from their more typical usages, and may even be used in disparate contexts in the copyright realm itself with different meanings.” The result is that the relationships between different parties in the music industry as represented in the image above are not always intuitive.

The rise of the administrative state over the past century increased government regulation in many areas, including copyright law. Specific exceptions to each right have been added over the decades. And, since the early 1900’s, Congress has increasingly regulated content industries directly through compulsory licenses – government set rates for certain specified uses. The administration of these compulsory licenses was often delegated to new or existing parties either by law or through industry practices. Several lines on the image above exist solely because of this regulation.

As with any industry, the music industry has grown more compartmentalized, with intermediaries specializing in individual roles within the complex system. One example of this division of labor is the formation of performing rights organizations (PROs) – groups which grant the right to publicly perform the songs of thousands of songwriters and music publishers to radio stations, tv networks, bars and restaurants. In a way, while intermediaries like PROs add another hub in the music industry, they reduce complexity overall; without them, each individual songwriter/publisher would need to form a relationship with each individual performance outlet.

Lessons to Learn

Certainly, the music industry and copyright law are complex – a result stemming from numerous factors. But mere complexity is not a defect. Looking at this image and saying, “Ha ha, it looks like spaghetti,” provides no insight. Comparing the current Copyright Act to the Tax Code 4Joseph P. Liu, Regulatory Copyright, 83 North Carolina Law Review 87, 88 (2004). begs the question: the less words, the better the law. Instead, we should look at the music industry and copyright law independent of their complexity. Is the current music industry sustainable? Is copyright law effective in fulfilling its purpose? These are far better questions then, “At what point do people say it’s time to scrap this mess and start from scratch?”

The complexity of the music industry does raise a valid point, though. Does a complex system like this create barriers to new players to join the game? The chart above was originally created by a company named Pure to announce its launch of a new streaming music service. It was used to illustrate the challenges the company faced in creating the service. The company’s CEO claimed it took three hours for someone to explain the chart to him, lamenting that “There were times along the way I almost gave up.” The conclusion often reached is that if companies like Pure – who “start from a fundamental position that we respect copyright” – give up when faced with untangling the web of copyright law, then services that don’t respect copyright will take their place. The law is firmly on content industy’s side, and enforcement efforts are increasing, but at the same time, lawmakers and the music industry must continue to look at ways to reduce the negative impacts of copyright’s complexity. 5Shameless plug: I propose one such way in my recent paper, Copyright Reform Step Zero.

References

| ↑1 | Note: the image is meant to illustrate the UK music industry, which is largely similar to the US industry but does have some differences. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Hypothetically speaking. The reality may be different since US federal copyright law did not recognize sound recordings as copyrightable subject matter until 1972, though some states and the UK did before then. |

| ↑3 | Nimmer on Copyright discusses this issue in its introduction: “An even more fundamental problem, with ramifications for both judge-made rules and legislation, is that words are often used in the copyright context with special meaning, at variance from their more typical usages, and may even be used in disparate contexts in the copyright realm itself with different meanings.” |

| ↑4 | Joseph P. Liu, Regulatory Copyright, 83 North Carolina Law Review 87, 88 (2004). |

| ↑5 | Shameless plug: I propose one such way in my recent paper, Copyright Reform Step Zero. |