Today’s guest post comes from Copyhype contributor Devlin Hartline. Cross-posted on the Law Theories blog.

Love them or loathe them, notorious copyright enforcer Righthaven presents an interesting question of law: Does Righthaven, the assignee of a copyright plus the accrued causes of action, have standing to sue for past infringements if it grants back to its assignor, Stephens Media, an exclusive license to exploit the copyright? The district courts that have considered this question have all found that such an arrangement does not leave Righthaven with an ownership interest sufficient to have standing. I think they’re wrong.

Last month, Righthaven finally had its day before the Ninth Circuit when it participated in oral arguments in two of its appeals (audio available here). 1The Ninth Circuit joined two of Righthaven’s appeals for purposes of oral arguments: Righthaven v. Hoehn and Righthaven v. DiBiase. These appeals almost didn’t happen. Back in late 2011, a district court granted a motion to appoint a receiver made by one of Righthaven’s defendants, Wayne Hoehn. The court ordered Righthaven’s intellectual and tangible property to be assigned to the receiver so that it could be sold to partially satisfy Hoehn’s judgment against Righthaven. Despite the fact that the receivership was explicitly for this limited purpose, 2The motion that was granted provides the following summary: “Defendant Wayne Hoehn (‘Hoehn’), through his attorneys, brings this motion seeking this Court to order the appointment of a receiver to which Plaintiff Righthaven LLC (‘Righthaven’) shall assign all of its intellectual property and other intangible property, which the receiver shall auction in order to partially satisfy Hoehn’s judgment and writ of execution entered against Righthaven. (Docs. # 44, 59)â€; Hoehn also sought that “all objects, items, or other property belonging to Righthaven should be delivered to the Receiver for auction,†though it was “presumed that Righthaven owns little tangible property of material value.†the receiver had more grandiose plans. When she found out that Righthaven CEO Steven Gibson was planning to appeal Hoehn’s victory, the receiver reported to the district court that she had taken over the company, fired Gibson, and fired the counsel Gibson had lined up to prosecute the appeal.

The receiver argued that, given Righthaven’s poor chances of success on appeal, it was in the best interests of the receivership to cease the appeals process. She also claimed, somewhat circularly, that since Righthaven no longer owned any of the copyrights that it had sued over, it had no standing to pursue its appeals before the Ninth Circuit. 3The receiver argued: “Moreover, as Righthaven no longer owns any of the copyright rights it originally sued Hoehn and others for infringing, it no longer possesses standing to pursue its claims before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals or any other Court. (Doc. # 90) This further affirms my view that the receivership estate’s best interests at this point are served by making the estate as productive as possible for its many creditors, and by terminating the existing appeals.†The very issue on appeal, of course, was whether Righthaven owned the copyrights and had standing to sue, and it is elementary that a party has standing to appeal a district court’s determination that it does not have standing to sue. 4See, e.g., In re Pittsburgh & L.E.R. Co. Sec. & Antitrust Litig., 543 F.2d 1058, 1064 (3d Cir. 1976) (“A party denied standing to sue, or to intervene, or to object, may obviously appeal such a determination. The question of standing does not go to whether or not the appeal should be heard, but rather to its merits.â€). Exercising her mandate that she thought gave her “broad, almost limitless equitable powers,†the receiver sought to have the court ratify her decision to torpedo the appeals. The district court rebuffed the receiver’s request, clarifying that the receivership was for the limited purpose of selling Righthaven’s assets—not for the purpose of firing Righthaven’s counsel and withdrawing its appeals. 5Docket entry 117 provides in part: “The Court clarifies the scope of the Receivership and confirms the Receivership was for the limited purpose to dispose of assets to satisfy the judgment, not to fire counsel handling the appeal and not to take any other action regarding Righthaven’s appeal.â€

Having won that small victory in the district court, Righthaven’s fate is now being decided by a panel of the Ninth Circuit. The legal question presented on the standing issue is actually a rather straightforward and simple application of the law. Yet, I believe that every court that has so far addressed the issue has approached it in the wrong way. I think the blame lies mainly with Righthaven’s poor briefing of the somewhat metaphysical doctrine of copyright ownership, but I think the judiciary’s unfamiliarity with the issues has played a role as well. In this article, I’ll explain why I think the Righthaven standing issue is simple and why I think Righthaven has standing to sue for past infringements.

Silvers v. Sony

In the Ninth Circuit, where the Righthaven appeals are being prosecuted, the Silvers v. Sony case controls the standing analysis. In the district court, the plaintiff, Nancey Silvers, claimed that the defendant, Sony Pictures, had infringed the copyright in a television movie she had written on a work-for-hire basis with the production company Frank & Bob Films. 6See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss, No. 00-cv-6386, 2001 WL 36127624 (C.D. Cal. Jan. 25, 2001). Since Silvers had no ownership interest in the copyright by way of her work-for-hire contract, 7See 17 U.S.C.A. 201(b) (West 2013) (“In the case of a work made for hire, the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author for purposes of this title, and, unless the parties have expressly agreed otherwise in a written instrument signed by them, owns all of the rights comprised in the copyright.â€). Frank & Bob Films assigned to her the accrued causes of action so that she could pursue the alleged infringement on her own. Sony argued that Silvers was not a “legal or beneficial owner†under the Act and thus had no standing to sue. 8See 17 U.S.C.A. § 501(b) (West 2013) (“The legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right under a copyright is entitled . . . to institute an action for any infringement of that particular right committed while he or she is the owner of it.â€).

Silvers, on the other hand, cited the copyright treatise Nimmer on Copyright which at the time provided that “the assignee of an accrued infringement cause of action has standing to sue without the need to join his assignor, even if the latter retains ownership of all other rights under the copyright.†9Silvers, 2001 WL 36127624 at *1 (quoting Nimmer on Copyright § 12.02[B]) (internal quotations omitted). The district court, citing Nimmer, the text of the Act, and public policy, sided with Silvers, holding that she had standing to sue even though owning only the accrued causes of action: “Where the cause of action has already accrued, though, the claim is akin to a vested right, and the Court sees no reason why a copyright holder, like any other property owner, would not have the ability to assign that right.†10Id. at *2.

A few months later, the district court granted Sony’s motion for interlocutory appeal to the Ninth Circuit on the standing issue. 11See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., Order Granting Defendants’ Motion for Interlocutory Appeal, No. 00-cv-6386, 2001 WL 36127626 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 29, 2001). There, the appellate panel noted that it was a matter of first impression in the circuit “whether an accrued cause of action for copyright infringement may be assigned to a third party, without any other copyright rights accompanying the assignment.†12Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., 330 F.3d 1204, 1206 (9th Cir. 2003). The panel echoed the reasoning of the district court below, citing Nimmer, the text of the Act, and public policy, to conclude that:

Nothing in the statute prohibits the legal or beneficial owner of the exclusive right under copyright from assigning an accrued cause of action for infringement of that right. Such an assignment is like assignment of any other chose in action under contract theory. Nothing in the language of the statute prohibits or restricts an assignee of an accrued infringement cause of action from bringing a copyright infringement action. 13Id. at 1208.

Unhappy with its defeat before the district court and the appellate panel, Sony petitioned for and was granted a rehearing en banc. 14See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., 370 F.3d 1252 (9th Cir. 2004). There, the en banc majority reversed the district court, holding instead that an assignee of accrued causes of action who has no other legal of beneficial ownership in the copyright has no standing to sue for past infringements. 15See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., 402 F.3d 881 (9th Cir. 2005).

The majority started its analysis by noting that standing to sue in copyright, a creature of federal statute, is authorized by Section 501(b) of the Copyright Act which provides:

The legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right under a copyright is entitled . . . to institute an action for any infringement of that particular right committed while he or she is the owner of it. 1617 U.S.C.A. § 501(b) (West 2013).

The majority reasoned that, under the plain language of the statute, one must be a “legal or beneficial owner†of the exclusive right at issue in order to have standing to sue. The court deduced that since an accrued cause of action is not one of the listed rights in Section 106, its holder is not a “legal or beneficial owner†of the copyright unless she also has some other ownership interest in it. The majority went on to examine the legislative history of the Act, patent law, and opinions from other circuits to conclude that “[t]he bare assignment of an accrued cause of action is impermissible under 17 U.S.C. § 501(b). Because that is all Frank & Bob Films conveyed to Silvers, Silvers was not entitled to institute and may not maintain this action against Sony†for the alleged infringement. 17Silvers, 402 F.3d at 890.

It should be noted that the majority did not see a problem with assigning an accrued cause of action, finding the practice to be consistent with the Copyright Act and its constitutional purpose. Moreover, the majority provided the rationale for allowing such transfers: “When one acquires a copyright that has been infringed, one is acquiring a copyright whose value has been impaired. Consequently, to receive maximum value for the impaired copyright, one must also convey the right to recover the value of the impairment by instituting a copyright action.†18Id. at 890 n.1 Thus, it was not the assignment of the accrued causes of action that posed a problem for the majority. The problem was, in the majority’s opinion, that such an assignee was not also a “legal or beneficial owner†entitled to institute an action under Section 501(b) of the Act.

Personally, I think the majority’s analysis is rather poor—while purporting to prevent a circuit split, 19See id. (“[T]he creation of a circuit split would be particularly troublesome in the realm of copyright.â€). the majority in fact only caused one. 20See Prather v. Neva Paperbacks, Inc., 410 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1969); Eden Toys, Inc. v. Florelee Undergarment Co., Inc., 697 F.2d 27 (2d Cir. 1982); ABKCO Music, Inc. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 944 F.2d 971 (2d Cir. 1991). I’ll sketch out some of the basic problems with the decision here, but the topic is complicated and rightfully deserving of its own post. The majority was correct to note that an accrued cause of action is assignable. Such was the case under the 1909 Act as it is now under the 1976 Act. This comports with the common law view generally that an accrued cause of action for a property tort is itself a property interest that is freely assignable. 21See, e.g., City of Cincinnati v. Hafer, 49 Ohio St. 60, 66 (1892) (“Mere personal torts die with the party, and are not assignable; but where the action is brought for damage to the estate, and not for injury to the person, personal feelings, or character, and the right of action survives to the personal representative, it may be assigned so as to pass an interest to the assignee.â€); Comegys v. Vasse, 26 U.S. 193, 213 (1828) (“In general, it may be affirmed, that mere personal torts, which die with the party, and do not survive to his personal representative, are not capable of passing by assignment; and that vested rights ad rem and in re, possibilities coupled with an interest, and claims growing out of, and adhering to property, may pass by assignment.â€); 6A C.J.S. Assignments § 43 (“A chose in action or claim, whether arising in tort or contract, is generally assignable, as a chose in action is personal property.â€). The twist added to this general rule by the majority is that it read Section 501(b) as mandating that the accrued causes of action must be accompanied by an ownership interest in the copyright, else the holder is not a “legal or beneficial owner†with statutory standing to sue under the Copyright Act.

The majority misreads Section 501(b). On its face, the statute appears to say that an accrued cause of action is not assignable since it authorizes the “legal or beneficial owner . . . to institute an action for any infringement of that particular right committed while he or she is the owner of it.†But, as the majority itself demonstrates, courts do not interpret it this way. Instead, the statute is read to mean that a cause of action accrues to whomever is the “legal or beneficial owner†at the time the cause of action accrues. Once the cause of action accrues to the “legal or beneficial owner,†it becomes a vested property interest that can be assigned to another, as the majority rightly concedes. What the majority misses is that such an assignee has standing to sue because he is a “legal or beneficial owner†of the underlying exclusive right, even if he is conveyed no other ownership interest in it.

There’s two different ways to look at this. The first is to realize that an assignee stands in the shoes of his assignor. 22See, e.g., 6 Am. Jur. 2d Assignments § 134 (“Although an assignee acquires the rights of the assignor, including the right to enforce the assigned obligation, he or she does not sue in his or her own right, but stands in the shoes of the assignor.â€); RTC Commercial Loan Trust 1995-NP1A v. Winthrop Mgmt., 923 F.Supp. 83, 88 (E.D. Va. 1996) (“[I]t is a fundamental maxim of common law that the assignee stands in the shoes of the assignor . . . .â€). The courts allow the assignee to take on his assignor’s position, so that if the assignor was the “legal or beneficial owner†at the time the cause of action accrued, the assignee steps into his shoes and can claim to have been such an owner as well. The second way to look at this is to recognize that an owner of an accrued cause of action is himself a “legal or beneficial owner†in his own right since an accrued cause of action is an in rem property interest in the underlying exclusive right. Not only can he claim his assignor’s ownership status as it relates back to when the cause of action accrued, he can claim his own ownership status for the purpose of standing.

This is demonstrated in the case law. The general rule is that, unless a copyright assignment expressly includes the accrued causes of action, an assignee of a copyright—even one who obtains otherwise full legal and equitable ownership—is not also transferred the accrued causes of action and does not have standing to sue for past infringements. 23See, e.g., ABKCO Music, Inc. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 944 F.2d 971, 980 (2d Cir. 1991) (“Thus, a copyright owner can assign its copyright but, if the accrued causes of action are not expressly included in the assignment, the assignee will not be able to prosecute them.â€); Giddings v. Vision House Prod., Inc., 584 F.Supp.2d 1222, 1229 (D. Ariz. 2008) (“Copyright assignments do not include accrued causes of action unless they are expressly included in the assignment.â€); 3-12 Nimmer on Copyright § 12.02 (“[O]nly the grantor, not the grantee, has standing to sue for pre-grant infringement, even if the action is filed after the grant has been executed.â€). Instead, the assignor, who no longer holds any other ownership interest in the copyright, is alone permitted to sue for past infringements. 24See, e.g., Skor-Mor Products, Inc. v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 1982 WL 1264 (S.D.N.Y. May 12, 1982) (“Similarly, it is the assignor, not the assignee, who has standing to sue for infringing acts which occurred prior to the assignment of copyright.â€); ABKCO Music, Inc. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 944 F.2d 971, 980 (2d Cir. 1991) (“Rather, the assignee is only entitled to bring actions for infringements that were committed while it was the copyright owner and the assignor retains the right to bring actions accruing during its ownership of the right, even if the actions are brought subsequent to the assignment.â€); M.J. Golden & Co. v. Pittsburgh Brewing Co., 137 F.Supp. 455, 457 (D. Pa. 1956) (“[E]ven though there has been a sale of the copyright this does not prevent the owner at the time of the alleged infringement from suing for previous damages it alleges to have sustained while it was the owner.â€). Under the majority’s logic, this should not be possible since it reasons that a party who holds only the accrued causes of action and no other ownership interest is not a “legal or beneficial owner†under Section 501(b). The majority conspicuously fails to address this point.

Nor does the majority address another wrinkle in the doctrine which provides that a copyright owner who otherwise parts with legal and equitable ownership of an exclusive right, while retaining the right to receive royalties from its future exploitation, has standing to sue for later occurring infringements of that right. 25See, e.g., Cortner v. Israel, 732 F.2d 267, 271 (2d Cir. 1984) (“When a composer assigns copyright title to a publisher in exchange for the payment of royalties, an equitable trust relationship is established between the two parties which gives the composer standing to sue for infringement of that copyright. Otherwise the beneficial owner’s interest in the copyright could be diluted or lessened by a wrongdoer’s infringement.â€) (internal citations omitted). Under the majority’s reasoning, since the right to receive royalties is not an enumerated right under Section 106, such a rightholder would not have standing to sue. But Congress clearly intended otherwise by explicitly providing in the legislative history of the Act that such a party would be a “beneficial owner†of the underlying exclusive right with standing to sue for its infringement. 26See H.R. Rep. No. 1476, 159 (“A ‘beneficial owner’ for this purpose would include, for example, an author who had parted with legal title to the copyright in exchange for percentage royalties based on sales or license fees.â€). The simple explanation for this is that, like the holder of the accrued causes of action, the holder of the right to receive royalties has an in rem interest in the exclusive right that makes him the “legal or beneficial owner†of it.

While the majority was perhaps correct to note that Section 501(b) limits standing to sue to only a “legal or beneficial owner†of the underlying exclusive right, it somehow missed the jurisprudential gloss that such ownership may relate back in time to that of his assignor’s ownership, such as with an assignee of an accrued cause of action, or may include one who otherwise has no present legal or beneficial ownership interest, such as with an assignor of all legal and beneficial ownership who retains the accrued causes of action or retains the right to receive royalties. Thus, the question is not, as the majority perceived it, whether he currently controls the exploitation of the exclusive right. The question is whether he holds an in rem ownership interest in the exclusive right, whether via the “shoes†of his assignor or in his own right.

The majority’s reasoning makes other critical mistakes, such as misinterpreting the legislative history and misreading the case law from other circuits. But for better or for worse, Silvers is the law in the Ninth Circuit and a holder of an accrued cause of action has no standing to sue unless he also holds some other legal or beneficial ownership in the underlying exclusive right.

The Righthaven Assignment

It was against this legal backdrop that Righthaven and Stephens Media executed the contract that’s at issue here. The contract actually consists of two parts, a “Copyright Assignment†and a supplemental agreement militaristically dubbed the “Strategic Alliance Agreement†(“SAAâ€). The Copyright Assignment in relevant part provides:

Stephens Media hereby transfers, vests and assigns the work depicted in Exhibit A, attached hereto and incorporated herein by this reference (the “Work”), to Righthaven, subject to Stephens Media’s rights of reversion, all copyrights requisite to have Righthaven recognized as the copyright owner of the Work for purposes of Righthaven being able to claim ownership as well as the right to pursue past, present and future infringements of the copyright in and to the Work.

By itself, the Copyright Assignment conveys ownership of the underlying exclusive rights and the accrued causes of action to Righthaven, which under the majority opinion in Silvers would grant Righthaven standing to sue for past infringements. In fact, district courts that looked at only the Copyright Assignment had no trouble finding that it granted Righthaven standing to sue. 27See, e.g., Righthaven LLC v. Dr. Shezad Malik Law Firm P.C., No. 10-cv-0636, 2010 WL 3522372, *2 (D. Nev. Sept. 2, 2010) (Hunt, C.J.) (“Furthermore, the assignment in question (which Plaintiff has attached to its opposition) clearly assigns both the exclusive copyright ownership, together with accrued causes of action, i.e., infringements past, present and future. While Courts have denied standing to bring an action on an accrued claim where just the copyright is owned or just the cause of action has been assigned, where there is an assignment of both the copyright, and any accrued causes of action, the courts have held that the assignee of both can bring an action even for infringing activities which occurred before the assignment. Thus, in this instance, Plaintiff has standing to sue, even for an infringement which preceded the assignment, because that right was specifically assigned with the exclusive assignment of the copyright itself.â€) (internal citations omitted). Thus, it is with the addition of the SAA to the Copyright Assignment that the Righthaven standing issue arises.

The provision of the SAA which has received the most attention is Section 7.2, which in relevant part provides:

Despite any such Copyright Assignment, Stephens Media shall retain (and is hereby granted by Righthaven) an exclusive license to Exploit the Stephens Media Assigned Copyrights for any lawful purpose whatsoever and Righthaven shall have no right or license to Exploit or participate in the receipt of royalties from the Exploitation of the Stephens Media Assigned Copyrights other than the right to proceeds in association with a Recovery.

Other sections of the SAA have received notice too, such as Section 5 which provides that Righthaven is to split recoveries minus costs with Stephens Media and Section 8 which provides Stephens Media with a reversionary right in the copyrights assigned to Righthaven, but Section 7.2 is the one that’s caused the most fuss.

The first serious blow to Righthaven came in the Democratic Underground case, wherein Chief Judge Roger Hunt noted that the SAA was “highly relevant to Righthaven’s standing in this and a multitude of other pending Righthaven cases.†28Righthaven LLC v. Democratic Underground, LLC, 791 F.Supp.2d 968, 971 (D. Nev. 2011) (Hunt, C.J.). In his opinion, the SAA “expressly denies Righthaven any rights . . . other than the bare right to bring and profit from copyright infringement actions.†29Id. at 972. He reasoned that under Section 7.2 of the SAA, Righthaven received no other ownership interest in the underlying exclusive rights: “The plain and simple effect of this section was to prevent Righthaven from obtaining, having, or otherwise exercising any right other than the mere right to sue as Stephens Media retained all other rights.†30Id. (italics in original).

As to Righthaven’s argument that the SAA did not alter its standing under the clear import of the Copyright Agreement, Chief Judge Hunt quipped: “This conclusion is flagrantly false—to the point that the claim is disingenuous, if not outright deceitful. The entirety of the SAA was designed to prevent Righthaven from becoming an owner of any exclusive right in the copyright . . . .†31Id. at 973 (italics in original; internal quotations omitted). He then held that under the majority opinion in Silvers, Righthaven, as the holder of only the accrued causes of action, did not have standing to sue: “In reality, Righthaven actually left the transaction with nothing more than a fabrication since a copyright owner cannot assign a bare right to sue after Silvers.†32Id.

Six days after Chief Judge Hunt issued his seminal opinion in Democratic Underground, the district court in the Hoehn case followed suit, finding that the “carveouts†in the SAA “deprive Righthaven of any of the rights normally associated with ownership of an exclusive right necessary to bring suit for copyright infringement and leave Righthaven no rights except to pursue infringement actions . . . .†33Righthaven, LLC v. Hoehn, 792 F.Supp.2d 1138, 1146 (D. Nev. 2011) (Pro, J.). The day after that, Chief Judge Hunt issued an opinion in the DiBiase case, finding again that the SAA left Righthaven without “the exclusive rights necessary to maintain standing in a copyright infringement action,†and incorporating his opinion in Democratic Underground by reference. 34Righthaven, LLC v. DiBiase, No. 10-cv-01343, 2011 WL 2473531, *1 (D. Nev. June 22, 2011) (Hunt, C.J.). It is these opinions in the Hoehn and DiBiase cases that form the basis of Righthaven’s appeals before the Ninth Circuit.

Why Righthaven Has Standing

Much like the majority in Silvers failed to recognize that the holder of only the accrued causes of action is a “legal or beneficial owner†of the underlying exclusive right, so too have the district courts that have analyzed the Righthaven standing issue failed to recognize that Righthaven has an ownership interest in the underlying exclusive rights in addition to the accrued causes of action. As discussed above, the Copyright Assignment grants to Righthaven ownership of the underlying exclusive rights plus ownership of the accrued causes of action. The SAA supplements the Copyright Assignment, and it provides that “Stephens Media shall retain (and is hereby granted by Righthaven) an exclusive license†to exploit the exclusive rights and to keep the royalties to itself. The mistake made by the district courts is interpreting this simultaneous retention by (or license back to) Stephens Media as divesting Righthaven of whatever ownership interests in the underlying exclusive rights that the Copyright Assignment may have granted it.

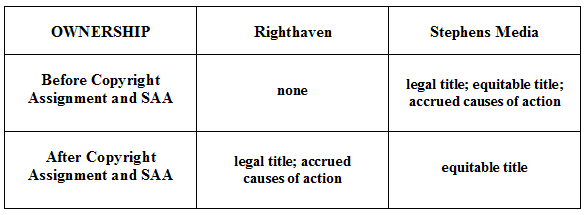

The Copyright Assignment and SAA instead should be read as dismembering the ownership such that Righthaven became the legal owner and Stephens Media remained the beneficial owner of the underlying exclusive rights. The key to understanding the Righthaven standing issue is to recognize that legal ownership of an exclusive right can be held by one in trust for another who is a beneficial owner. In such a trust relationship, the legal owner holds legal title while the beneficial owner holds equitable title to the underlying exclusive rights. 35See, e.g., Black v. Henry G. Allen Co., 42 F. 618, 621 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1890) ([T]here is no restriction upon the power of the proprietor to assign or transfer, in equity, an exclusive right to use the copyrighted book in a particular manner or for particular purposes upon such terms and conditions as may be agreed upon. In such case the legal title remains in the proprietor; and a beneficial interest, to the extent which is agreed upon, vests in the other party, who has acquired an equitable right in the copyright, and who will be properly styled an assignee of an equitable interest.â€) (internal quotations omitted); Bisel v. Ladner, 1 F.2d 436 (3d Cir. 1924) (“The legal title to a copyright vests in the person in whose name the copyright is taken out. It may, however, be held by him in trust for the true owner . . . .â€); Manning v. Miller Music Corp., 174 F.Supp. 192, 195 (S.D.N.Y. 1959) (“[T]he courts recognize that legal title to a copyright may be in one person and equitable title in another. Thus, one may be a ‘proprietor’ of a copyright if he holds legal title, though equitable title may be in another wither expressly or as trustee ex malificio.â€) (internal citations omitted); Silverman v. Sunrise Pictures Corp., 273 F. 909, 914 (2d Cir. 1921) (“There is nothing in the nature of copyright forbidding a separation between the legal and equitable titles; one may hold in trust for others . . . .â€); Arachnid, Inc. v. Merit Indus., Inc., 939 F.2d 1574, 1578 n.3 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (discussing patents) (“Equitable title may be defined as the beneficial interest of one person whom equity regards as the real owner, although the legal title is vested in another.â€) (internal quotations omitted); Matter of Southmark Corp., 49 F.3d 1111, 1117-18 (5th Cir. 1995) (“In a trust relationship, by contrast, the law actually divides the bundle of rights in the property; the trustee holds legal title while the beneficiary possesses an equitable title or property interest.â€). The Copyright Assignment and SAA simply transferred to Righthaven legal title to the underlying exclusive rights and the accrued causes of action, while Stephens Media retained or was simultaneously granted back—it matters not which way you look at it since both achieve the same result—the equitable title to the underlying exclusive rights.

The following table illustrates the legal and beneficial ownership interests held by Righthaven and Stephens Media before and after the Copyright Assignment and SAA:

The whole point of the Copyright Assignment and SAA was to comply with the dictate in Silvers. Righthaven was not assigned only the accrued causes of action, but it was assigned legal title to the underlying exclusive rights as well. Thus, as the legal owner of the underlying exclusive rights and the accrued causes of action, Righthaven has standing to sue for past infringements under the rule declared by the Silvers majority. The very purpose of the Copyright Assignment and SAA was to give both legal title and the accrued causes of action to Righthaven while Stephens Media kept the equitable title for itself. The parties did exactly what Silvers said to do.

Contrary to Chief Judge Hunt’s quip that Righthaven’s representation about the SAA was “flagrantly false—to the point that the claim is disingenuous, if not outright deceitful,†I think Righthaven’s claim that the SAA did not affect its standing was correct. The reason is simple: The SAA did not divest Righthaven of the legal title or the accrued causes of action that it had been granted in the Copyright Assignment. To be sure, the SAA established in the underlying exclusive rights both in personam contractual rights and in rem property interests, but none of those equitable interests changed the fact that Righthaven still held its legal interests and the accrued causes of action. 36See, e.g., Marrone v. Washington Jockey Club of Dist. of Columbia, 227 U.S. 633, 636 (1913) (“A contract binds the person of the maker, but does not create an interest in the property that it may concern, unless it also operates as a conveyance.â€); Matter of Southmark Corp., 49 F.3d 1111, 1117-18 (5th Cir. 1995) (“At the outset, it is important to distinguish generally between two types of ‘equitable interests.’ In a contractual (or debtor-creditor) relationship, the creditor may possess an ‘equitable claim’ to property actually owned by the debtor, but there is no division of ownership or title in the property at issue; the debtor is entirely free to dispose of the property as he sees fit. In a trust relationship, by contrast, the law actually divides the bundle of rights in the property; the trustee holds legal title while the beneficiary possesses an equitable title or property interest.â€).

The district courts that have looked at the Righthaven standing issue have misconstrued the difference between an assignment, which typically transfers both legal and equitable title, and an exclusive license, which transfers only equitable title. 37See, e.g., Presley’s Estate v. Russen, 513 F.Supp. 1339, 1350 (D.N.J. 1981) (“An assignment passes legal and equitable title to the property while a license is mere permission to use. Assignment is the transfer of the whole of the interest in the right while in a license the owner retains the legal ownership of the property.â€). The difference is critical. Courts are familiar with the concept of an exclusive licensee, and an entire body of federal common law has developed around this type of ownership interest. But antiquated concepts, such as the idea that an exclusive licensee holds equitable title, tend to get lost—though some remnants appear in the 1976 Act. For example, Section 301(a) preempts “all legal or equitable rights that are equivalent to any of the exclusive rights within the general scope of copyright as specified by section 106 . . . .†3817 U.S.C.A. § 301(a) (West 2013) (“On and after January 1, 1978, all legal or equitable rights that are equivalent to any of the exclusive rights within the general scope of copyright as specified by section 106 in works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression and come within the subject matter of copyright as specified by sections 102 and 103, whether created before or after that date and whether published or unpublished, are governed exclusively by this title. Thereafter, no person is entitled to any such right or equivalent right in any such work under the common law or statutes of any State.”). This presupposes the existence of both legal and equitable rights in a copyright.

Another example is Section 501(b)’s provision that a “legal or beneficial owner†has standing to sue. Courts often indicate that both legal owners and exclusive licensees have standing under this section, but they don’t make the connection that the legal titleholder is the “legal owner†while the exclusive licensee, who holds equitable title, is the “beneficial owner.†Back before the merger of law and equity, whether one’s title was legal or equitable mattered significantly since only the legal owner could institute an action in a court of law. Equitable owners, such as an exclusive licensee, had to bring suit in a court of equity. 39See, e.g., Ted Browne Music Co. v. Fowler, 290 F. 751, 753 (2d Cir. 1923) (“The owner of the equitable title is not a mere licensee [i.e., a nonexclusive licensee], and he may sue in equity, particularly where the owner of the legal title is an infringer, or one of the infringers, thus occupying a position hostile to the plaintiff.â€); Cortner v. Israel, 732 F.2d 267, 271 (2d Cir. 1984) (“Prior to the adoption of the 1976 Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 101, 501(b), the beneficial owner, in order to have standing to sue the infringer, was required to join the owner of the copyright as a defendant, alleging that the latter had refused after demand to sue.â€); Buck v. Virgo, 22 F.Supp. 156, 157 (W.D.N.Y. 1938) (“The rights of a licensee under a copyright do not depend upon legal title. A licensee has no right to sue in his own name for infringement. The reason for the necessity of joining the owner of the copyright as plaintiff is that the owner has the legal title. This he holds in trust for the licensee.â€) (internal citations omitted); Stephens v. Howells Sales Co., 16 F.2d 805, 806 (S.D.N.Y. 1926) (“[A] licensee cannot bring suit for infringement of the copyright under which he holds his license in his own name; this for the reason that the copyright is, technically speaking, indivisible, the legal title remaining in the licensor and the licensee having merely an equitable title.â€). The merger of law and equity did away with the procedural, but not the substantive, differences between the two. 40See, e.g., Stainback v. Mo Hock Ke Lok Po, 336 U.S. 368, 382 n.2 (1949) (“Notwithstanding the fusion of law and equity by the Rules of Civil Procedure, the substantive principles of Courts of Chancery remain unaffected.â€); Railex Corp. v. Joseph Guss & Sons, Inc., 40 F.R.D. 119, 123 (D.D.C 1966) (“Initially, it should be mentioned that F.R.C.P. Rule 2 abolishes only the procedural distinctions but not the substantive distinctions between law and equity. The substantive distinctions between legal and equitable rights and remedies are still applicable in the Federal Courts, particularly with regard to the constitutional right to trial by jury ‘in suits at common law’ declared by the Seventh Amendment.â€). It was not until the 1976 Act that legal and equitable ownership interests were put on an equal footing for certain purposes, but—and this is crucial—they still remain distinct types of ownership interests.

The 1976 Act itself creates confusion over exactly what an exclusive license is. Section 101 provides:

A “transfer of copyright ownership†is an assignment, mortgage, exclusive license, or any other conveyance, alienation, or hypothecation of a copyright or of any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, whether or not it is limited in time or place of effect, but not including a nonexclusive license. 4117 U.S.C.A. § 101 (West 2013).

Thus, an assignment and an exclusive license are both a “transfer of copyright ownership.†What kind of ownership is transferred, the statute doesn’t say. The answer, developed in the case law that Section 101 merely ratified, is rather simple. Generally speaking, an assignment transfers legal and equitable title while an exclusive license transfers only equitable title. Both are a “transfer of copyright ownership,†as noted by Section 101, but the ownership interests transferred are different. Section 501(b) tells us this difference matters not in at least one significant way since both the “legal or beneficial owner†has standing to sue. The combined purpose of Sections 101 and 501(b) in the 1976 Act was to put an equitable titleholder, such as an exclusive licensee, on an equal footing with his licensor, the holder of legal title, for purposes of standing to sue. Much like the merger of law and equity had eliminated some of the procedural differences between legal and equitable ownership, the 1976 Act eradicated some of the substantive differences between the two as well.

That a licensor has a different type of ownership interest than his exclusive licensee was made clear in Gardner v. Nike, 42Gardner v. Nike, Inc., 279 F.3d 774 (9th Cir. 2002). an opinion out of the Ninth Circuit from 2002. There, Nike had granted an exclusive license to Sony Music, and the issue was whether Sony Music could then transfer its exclusive license to Gardner. The district court held that an exclusive licensee could not transfer his ownership interest to another without his licensor’s permission, and the Ninth Circuit agreed. The appellate panel relied on Section 201(d)(2) of the Act which provides that the owner of any particular exclusive right is entitled “to all of the protection and remedies accorded to the copyright owner†under the Act. 4317 U.S.C.A. § 201(d)(2) (West 2013) “Any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, including any subdivision of any of the rights specified by section 106, may be transferred as provided by clause (1) and owned separately. The owner of any particular exclusive right is entitled, to the extent of that right, to all of the protection and remedies accorded to the copyright owner by this title.”). Thus, reasoned the court, an exclusive licensee is vested with only the same “protections and remedies,†but not the same rights, as his licensor. If an exclusive licensee actually had legal ownership of the underlying exclusive right, his ability to transfer his interest to another would not be so saddled. Gardner v. Nike proves that exclusive licensees are not legal owners—at least in the Ninth Circuit where Righthaven is prosecuting its appeals.

There’s another layer that’s worth a mention. While Section 301(a) sounds in the general common law of property by referring to “legal or equitable rights,†Section 501(b) sounds in the general common law of trusts by referring to a “legal or beneficial owner.†The analogy to trust law is deliberate, for it was noted long ago that the licensor-exclusive licensee relationship is just like that of a trustee-beneficiary, with one holding legal title in trust for the other who is an equitable or beneficial owner of the property. 44See, e.g., Littlefield v. Perry, 88 U.S. 205, 223 (1874) (discussing patents) (“A court of equity looks to substance rather than form. When it has jurisdiction of parties it grants the appropriate relief without regard to whether they come as plaintiff or defendant. In this case the person who should have protected the plaintiff against all infringements has become himself the infringer. He held the legal title to his patent in trust for his licensees. He has been faithless to his trust, and courts of equity are always open for the redress of such a wrong. This wrong is an infringement.â€); Indep. Wireless Tel. Co. v. Radio Corp. of Am., 269 U.S. 459, 468-69 (1926) (discussing patents) (“If the owner of a patent, being within the jurisdiction, refuses or is unable to join an exclusive licensee as coplaintiff, the licensee may make him a party defendant by process, and he will be lined up by the court in the party character which he should assume. . . . This would seem to be in accord with general equity practice. . . . A cestui que trust may make an unwilling trustee a defendant in a suit to protect the subject of the trust.â€) (internal citations omitted). Trust law and copyright law have obviously gone their separate ways, but the analogy between the two remains and is at times instructive. It’s just not often that it’s mentioned anymore, much less so that it matters like it does here with Righthaven.

The analogy to trust law has not been totally lost, nor is it necessarily only an analogy, as demonstrated in the fifteen-year-old opinion in A. Brod, Inc. v. SK&I Co. 45A. Brod, Inc. v. SK&I Co., L.L.C., 998 F.Supp. 314 (S.D.N.Y. 1998). penned by then-District Judge Sonia Sotomayor. The facts there, somewhat similar to Righthaven’s, were that one party had assigned to the other “the entire right, title, and interest†to a particular copyright for the purpose of litigation. 46Id. at 318. The assignor, who wanted his copyright back, argued that the assignment really included only the legal title which his assignee held in trust for him as the equitable titleholder. The assignee denied the legal possibility of a trust, claiming that “trust-based rights in the copyright are preempted by the Copyright Act.†47Id. at 320. Judge Sotomayor did not agree:

[L]egal and equitable interest in a copyright may be held separately. As cases pre-dating the 1976 Copyright Act make clear, a copyright may constitute a proper trust res, with the trustee holding legal title to the copyright and the settlor retaining equitable title. The 1976 Copyright Act did not change this, but rather codified the notion that both the equitable, or “beneficial,†owner of a copyright and the legal owner have standing to sue for infringement. 48Id. at 325 (internal citations omitted).

Judge Sotomayor went on to analyze the assignment under New York state trust law, looking at whether it created an express or constructive trust such that the trustee-assignee’s subsequent transfer of his interest to a third party was subject to the assignor’s equitable interest in the trust. I think the soundness of this approach is dubious, as federal common and statutory law trumps state law when it comes to copyright ownership. The problem with analyzing copyright ownership under state trust law is that then concepts such as a good faith purchaser for value get injected into what is otherwise a federal common law scheme. The en banc Federal Circuit has rejected such an approach with patents, 49See Rhone Poulenc Agro, S.A. v. DeKalb Genetics Corp., 284 F.3d 1323, 1328 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (“In short, because of the importance of having a uniform national rule, we hold that the bona fide purchaser defense to patent infringement is a matter of federal law. Because such a federal rule implicates an issue of patent law, the law of this circuit governs the rule.”). and I think the same logic applies with equal force to copyrights. Copyright ownership issues should be decided applying federal copyright law which, while analogous to state trust law in some ways, is not the same thing.

So where does that leave us? Based on the oral arguments before the Ninth Circuit panel, things do not look good for Righthaven. One judge queried which party, Righthaven or Stephens Media, a prospective user of the copyright should approach for permission. Since it isn’t Righthaven, the judge implied, it means that Righthaven doesn’t really own the copyright and therefore does not have standing to sue. But this line of questioning misses the fact that there’s two types of ownership interests in a copyright, legal and equitable. A prospective user would contact the party who holds the equitable title to the exclusive right that he wishes permission to use since only that party controls the use of that right. But it should not be forgotten that legal ownership may reside in another—and that appears to be the case here with Righthaven.

Follow me on Twitter: @devlinhartline

References

| ↑1 | The Ninth Circuit joined two of Righthaven’s appeals for purposes of oral arguments: Righthaven v. Hoehn and Righthaven v. DiBiase. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | The motion that was granted provides the following summary: “Defendant Wayne Hoehn (‘Hoehn’), through his attorneys, brings this motion seeking this Court to order the appointment of a receiver to which Plaintiff Righthaven LLC (‘Righthaven’) shall assign all of its intellectual property and other intangible property, which the receiver shall auction in order to partially satisfy Hoehn’s judgment and writ of execution entered against Righthaven. (Docs. # 44, 59)â€; Hoehn also sought that “all objects, items, or other property belonging to Righthaven should be delivered to the Receiver for auction,†though it was “presumed that Righthaven owns little tangible property of material value.†|

| ↑3 | The receiver argued: “Moreover, as Righthaven no longer owns any of the copyright rights it originally sued Hoehn and others for infringing, it no longer possesses standing to pursue its claims before the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals or any other Court. (Doc. # 90) This further affirms my view that the receivership estate’s best interests at this point are served by making the estate as productive as possible for its many creditors, and by terminating the existing appeals.†|

| ↑4 | See, e.g., In re Pittsburgh & L.E.R. Co. Sec. & Antitrust Litig., 543 F.2d 1058, 1064 (3d Cir. 1976) (“A party denied standing to sue, or to intervene, or to object, may obviously appeal such a determination. The question of standing does not go to whether or not the appeal should be heard, but rather to its merits.â€). |

| ↑5 | Docket entry 117 provides in part: “The Court clarifies the scope of the Receivership and confirms the Receivership was for the limited purpose to dispose of assets to satisfy the judgment, not to fire counsel handling the appeal and not to take any other action regarding Righthaven’s appeal.†|

| ↑6 | See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., Order Granting in Part and Denying in Part Defendant’s Motion to Dismiss, No. 00-cv-6386, 2001 WL 36127624 (C.D. Cal. Jan. 25, 2001). |

| ↑7 | See 17 U.S.C.A. 201(b) (West 2013) (“In the case of a work made for hire, the employer or other person for whom the work was prepared is considered the author for purposes of this title, and, unless the parties have expressly agreed otherwise in a written instrument signed by them, owns all of the rights comprised in the copyright.â€). |

| ↑8 | See 17 U.S.C.A. § 501(b) (West 2013) (“The legal or beneficial owner of an exclusive right under a copyright is entitled . . . to institute an action for any infringement of that particular right committed while he or she is the owner of it.â€). |

| ↑9 | Silvers, 2001 WL 36127624 at *1 (quoting Nimmer on Copyright § 12.02[B]) (internal quotations omitted). |

| ↑10 | Id. at *2. |

| ↑11 | See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., Order Granting Defendants’ Motion for Interlocutory Appeal, No. 00-cv-6386, 2001 WL 36127626 (C.D. Cal. Mar. 29, 2001). |

| ↑12 | Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., 330 F.3d 1204, 1206 (9th Cir. 2003). |

| ↑13 | Id. at 1208. |

| ↑14 | See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., 370 F.3d 1252 (9th Cir. 2004). |

| ↑15 | See Silvers v. Sony Pictures Entm’t, Inc., 402 F.3d 881 (9th Cir. 2005). |

| ↑16 | 17 U.S.C.A. § 501(b) (West 2013). |

| ↑17 | Silvers, 402 F.3d at 890. |

| ↑18 | Id. at 890 n.1 |

| ↑19 | See id. (“[T]he creation of a circuit split would be particularly troublesome in the realm of copyright.â€). |

| ↑20 | See Prather v. Neva Paperbacks, Inc., 410 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1969); Eden Toys, Inc. v. Florelee Undergarment Co., Inc., 697 F.2d 27 (2d Cir. 1982); ABKCO Music, Inc. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 944 F.2d 971 (2d Cir. 1991). |

| ↑21 | See, e.g., City of Cincinnati v. Hafer, 49 Ohio St. 60, 66 (1892) (“Mere personal torts die with the party, and are not assignable; but where the action is brought for damage to the estate, and not for injury to the person, personal feelings, or character, and the right of action survives to the personal representative, it may be assigned so as to pass an interest to the assignee.â€); Comegys v. Vasse, 26 U.S. 193, 213 (1828) (“In general, it may be affirmed, that mere personal torts, which die with the party, and do not survive to his personal representative, are not capable of passing by assignment; and that vested rights ad rem and in re, possibilities coupled with an interest, and claims growing out of, and adhering to property, may pass by assignment.â€); 6A C.J.S. Assignments § 43 (“A chose in action or claim, whether arising in tort or contract, is generally assignable, as a chose in action is personal property.â€). |

| ↑22 | See, e.g., 6 Am. Jur. 2d Assignments § 134 (“Although an assignee acquires the rights of the assignor, including the right to enforce the assigned obligation, he or she does not sue in his or her own right, but stands in the shoes of the assignor.â€); RTC Commercial Loan Trust 1995-NP1A v. Winthrop Mgmt., 923 F.Supp. 83, 88 (E.D. Va. 1996) (“[I]t is a fundamental maxim of common law that the assignee stands in the shoes of the assignor . . . .â€). |

| ↑23 | See, e.g., ABKCO Music, Inc. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 944 F.2d 971, 980 (2d Cir. 1991) (“Thus, a copyright owner can assign its copyright but, if the accrued causes of action are not expressly included in the assignment, the assignee will not be able to prosecute them.â€); Giddings v. Vision House Prod., Inc., 584 F.Supp.2d 1222, 1229 (D. Ariz. 2008) (“Copyright assignments do not include accrued causes of action unless they are expressly included in the assignment.â€); 3-12 Nimmer on Copyright § 12.02 (“[O]nly the grantor, not the grantee, has standing to sue for pre-grant infringement, even if the action is filed after the grant has been executed.â€). |

| ↑24 | See, e.g., Skor-Mor Products, Inc. v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 1982 WL 1264 (S.D.N.Y. May 12, 1982) (“Similarly, it is the assignor, not the assignee, who has standing to sue for infringing acts which occurred prior to the assignment of copyright.â€); ABKCO Music, Inc. v. Harrisongs Music, Ltd., 944 F.2d 971, 980 (2d Cir. 1991) (“Rather, the assignee is only entitled to bring actions for infringements that were committed while it was the copyright owner and the assignor retains the right to bring actions accruing during its ownership of the right, even if the actions are brought subsequent to the assignment.â€); M.J. Golden & Co. v. Pittsburgh Brewing Co., 137 F.Supp. 455, 457 (D. Pa. 1956) (“[E]ven though there has been a sale of the copyright this does not prevent the owner at the time of the alleged infringement from suing for previous damages it alleges to have sustained while it was the owner.â€). |

| ↑25 | See, e.g., Cortner v. Israel, 732 F.2d 267, 271 (2d Cir. 1984) (“When a composer assigns copyright title to a publisher in exchange for the payment of royalties, an equitable trust relationship is established between the two parties which gives the composer standing to sue for infringement of that copyright. Otherwise the beneficial owner’s interest in the copyright could be diluted or lessened by a wrongdoer’s infringement.â€) (internal citations omitted). |

| ↑26 | See H.R. Rep. No. 1476, 159 (“A ‘beneficial owner’ for this purpose would include, for example, an author who had parted with legal title to the copyright in exchange for percentage royalties based on sales or license fees.â€). |

| ↑27 | See, e.g., Righthaven LLC v. Dr. Shezad Malik Law Firm P.C., No. 10-cv-0636, 2010 WL 3522372, *2 (D. Nev. Sept. 2, 2010) (Hunt, C.J.) (“Furthermore, the assignment in question (which Plaintiff has attached to its opposition) clearly assigns both the exclusive copyright ownership, together with accrued causes of action, i.e., infringements past, present and future. While Courts have denied standing to bring an action on an accrued claim where just the copyright is owned or just the cause of action has been assigned, where there is an assignment of both the copyright, and any accrued causes of action, the courts have held that the assignee of both can bring an action even for infringing activities which occurred before the assignment. Thus, in this instance, Plaintiff has standing to sue, even for an infringement which preceded the assignment, because that right was specifically assigned with the exclusive assignment of the copyright itself.â€) (internal citations omitted). |

| ↑28 | Righthaven LLC v. Democratic Underground, LLC, 791 F.Supp.2d 968, 971 (D. Nev. 2011) (Hunt, C.J.). |

| ↑29 | Id. at 972. |

| ↑30 | Id. (italics in original). |

| ↑31 | Id. at 973 (italics in original; internal quotations omitted). |

| ↑32 | Id. |

| ↑33 | Righthaven, LLC v. Hoehn, 792 F.Supp.2d 1138, 1146 (D. Nev. 2011) (Pro, J.). |

| ↑34 | Righthaven, LLC v. DiBiase, No. 10-cv-01343, 2011 WL 2473531, *1 (D. Nev. June 22, 2011) (Hunt, C.J.). |

| ↑35 | See, e.g., Black v. Henry G. Allen Co., 42 F. 618, 621 (C.C.S.D.N.Y. 1890) ([T]here is no restriction upon the power of the proprietor to assign or transfer, in equity, an exclusive right to use the copyrighted book in a particular manner or for particular purposes upon such terms and conditions as may be agreed upon. In such case the legal title remains in the proprietor; and a beneficial interest, to the extent which is agreed upon, vests in the other party, who has acquired an equitable right in the copyright, and who will be properly styled an assignee of an equitable interest.â€) (internal quotations omitted); Bisel v. Ladner, 1 F.2d 436 (3d Cir. 1924) (“The legal title to a copyright vests in the person in whose name the copyright is taken out. It may, however, be held by him in trust for the true owner . . . .â€); Manning v. Miller Music Corp., 174 F.Supp. 192, 195 (S.D.N.Y. 1959) (“[T]he courts recognize that legal title to a copyright may be in one person and equitable title in another. Thus, one may be a ‘proprietor’ of a copyright if he holds legal title, though equitable title may be in another wither expressly or as trustee ex malificio.â€) (internal citations omitted); Silverman v. Sunrise Pictures Corp., 273 F. 909, 914 (2d Cir. 1921) (“There is nothing in the nature of copyright forbidding a separation between the legal and equitable titles; one may hold in trust for others . . . .â€); Arachnid, Inc. v. Merit Indus., Inc., 939 F.2d 1574, 1578 n.3 (Fed. Cir. 1991) (discussing patents) (“Equitable title may be defined as the beneficial interest of one person whom equity regards as the real owner, although the legal title is vested in another.â€) (internal quotations omitted); Matter of Southmark Corp., 49 F.3d 1111, 1117-18 (5th Cir. 1995) (“In a trust relationship, by contrast, the law actually divides the bundle of rights in the property; the trustee holds legal title while the beneficiary possesses an equitable title or property interest.â€). |

| ↑36 | See, e.g., Marrone v. Washington Jockey Club of Dist. of Columbia, 227 U.S. 633, 636 (1913) (“A contract binds the person of the maker, but does not create an interest in the property that it may concern, unless it also operates as a conveyance.â€); Matter of Southmark Corp., 49 F.3d 1111, 1117-18 (5th Cir. 1995) (“At the outset, it is important to distinguish generally between two types of ‘equitable interests.’ In a contractual (or debtor-creditor) relationship, the creditor may possess an ‘equitable claim’ to property actually owned by the debtor, but there is no division of ownership or title in the property at issue; the debtor is entirely free to dispose of the property as he sees fit. In a trust relationship, by contrast, the law actually divides the bundle of rights in the property; the trustee holds legal title while the beneficiary possesses an equitable title or property interest.â€). |

| ↑37 | See, e.g., Presley’s Estate v. Russen, 513 F.Supp. 1339, 1350 (D.N.J. 1981) (“An assignment passes legal and equitable title to the property while a license is mere permission to use. Assignment is the transfer of the whole of the interest in the right while in a license the owner retains the legal ownership of the property.â€). |

| ↑38 | 17 U.S.C.A. § 301(a) (West 2013) (“On and after January 1, 1978, all legal or equitable rights that are equivalent to any of the exclusive rights within the general scope of copyright as specified by section 106 in works of authorship that are fixed in a tangible medium of expression and come within the subject matter of copyright as specified by sections 102 and 103, whether created before or after that date and whether published or unpublished, are governed exclusively by this title. Thereafter, no person is entitled to any such right or equivalent right in any such work under the common law or statutes of any State.”). |

| ↑39 | See, e.g., Ted Browne Music Co. v. Fowler, 290 F. 751, 753 (2d Cir. 1923) (“The owner of the equitable title is not a mere licensee [i.e., a nonexclusive licensee], and he may sue in equity, particularly where the owner of the legal title is an infringer, or one of the infringers, thus occupying a position hostile to the plaintiff.â€); Cortner v. Israel, 732 F.2d 267, 271 (2d Cir. 1984) (“Prior to the adoption of the 1976 Copyright Act, 17 U.S.C. §§ 101, 501(b), the beneficial owner, in order to have standing to sue the infringer, was required to join the owner of the copyright as a defendant, alleging that the latter had refused after demand to sue.â€); Buck v. Virgo, 22 F.Supp. 156, 157 (W.D.N.Y. 1938) (“The rights of a licensee under a copyright do not depend upon legal title. A licensee has no right to sue in his own name for infringement. The reason for the necessity of joining the owner of the copyright as plaintiff is that the owner has the legal title. This he holds in trust for the licensee.â€) (internal citations omitted); Stephens v. Howells Sales Co., 16 F.2d 805, 806 (S.D.N.Y. 1926) (“[A] licensee cannot bring suit for infringement of the copyright under which he holds his license in his own name; this for the reason that the copyright is, technically speaking, indivisible, the legal title remaining in the licensor and the licensee having merely an equitable title.â€). |

| ↑40 | See, e.g., Stainback v. Mo Hock Ke Lok Po, 336 U.S. 368, 382 n.2 (1949) (“Notwithstanding the fusion of law and equity by the Rules of Civil Procedure, the substantive principles of Courts of Chancery remain unaffected.â€); Railex Corp. v. Joseph Guss & Sons, Inc., 40 F.R.D. 119, 123 (D.D.C 1966) (“Initially, it should be mentioned that F.R.C.P. Rule 2 abolishes only the procedural distinctions but not the substantive distinctions between law and equity. The substantive distinctions between legal and equitable rights and remedies are still applicable in the Federal Courts, particularly with regard to the constitutional right to trial by jury ‘in suits at common law’ declared by the Seventh Amendment.â€). |

| ↑41 | 17 U.S.C.A. § 101 (West 2013). |

| ↑42 | Gardner v. Nike, Inc., 279 F.3d 774 (9th Cir. 2002). |

| ↑43 | 17 U.S.C.A. § 201(d)(2) (West 2013) “Any of the exclusive rights comprised in a copyright, including any subdivision of any of the rights specified by section 106, may be transferred as provided by clause (1) and owned separately. The owner of any particular exclusive right is entitled, to the extent of that right, to all of the protection and remedies accorded to the copyright owner by this title.”). |

| ↑44 | See, e.g., Littlefield v. Perry, 88 U.S. 205, 223 (1874) (discussing patents) (“A court of equity looks to substance rather than form. When it has jurisdiction of parties it grants the appropriate relief without regard to whether they come as plaintiff or defendant. In this case the person who should have protected the plaintiff against all infringements has become himself the infringer. He held the legal title to his patent in trust for his licensees. He has been faithless to his trust, and courts of equity are always open for the redress of such a wrong. This wrong is an infringement.â€); Indep. Wireless Tel. Co. v. Radio Corp. of Am., 269 U.S. 459, 468-69 (1926) (discussing patents) (“If the owner of a patent, being within the jurisdiction, refuses or is unable to join an exclusive licensee as coplaintiff, the licensee may make him a party defendant by process, and he will be lined up by the court in the party character which he should assume. . . . This would seem to be in accord with general equity practice. . . . A cestui que trust may make an unwilling trustee a defendant in a suit to protect the subject of the trust.â€) (internal citations omitted). |

| ↑45 | A. Brod, Inc. v. SK&I Co., L.L.C., 998 F.Supp. 314 (S.D.N.Y. 1998). |

| ↑46 | Id. at 318. |

| ↑47 | Id. at 320. |

| ↑48 | Id. at 325 (internal citations omitted). |

| ↑49 | See Rhone Poulenc Agro, S.A. v. DeKalb Genetics Corp., 284 F.3d 1323, 1328 (Fed. Cir. 2002) (“In short, because of the importance of having a uniform national rule, we hold that the bona fide purchaser defense to patent infringement is a matter of federal law. Because such a federal rule implicates an issue of patent law, the law of this circuit governs the rule.”). |

First off, great analysis of the issues and a wonderful read.

To me, it’s always seemed as if Righthaven was a classic case of the judges working backwards. It’s not a question of “Is this legal?” but “How can we make Righthaven’s unlawful?”

This applies to both the transfer issues and the fair use issues. I’m the first to admit that I’m not a Righthaven fan, but it seemed as if judges were going out of their way to nail them and ignoring both the law and the precedent, which is easy to do with something as complex and judgment-based as copyright.

Did Righthaven deserve to be beat down? Probably. But we didn’t deserve to be saddled with the questionable precedent that’s come from the cases…

Thanks, Jonathan! I’m reminded of the old adage that “bad facts make bad law.”

Pingback: A Closer Look at the Righthaven Standing Issue | Law Theories