On January 12, photographer Michael Kienitz asked the Supreme Court to review the Seventh Circuit’s decision in Kienitz v. Sconnie Nation. Sconnie Nation waived its brief, though the Media Institute filed an amicus brief in support of Kienitz.

The issue is fair use, specifically whether the Seventh Circuit split with the Second Circuit on the application of the “transformative use” test with its decision.

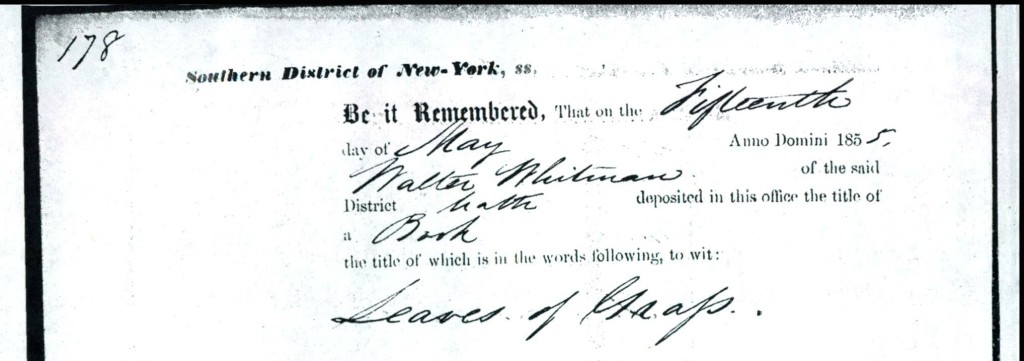

Kienitz takes place in the town of Madison, Wisconsin, where, several years ago, the Mayor sought to shut down an annual block party. Sconnie Nation, a novelty t-shirt maker, printed up a handful of t-shirts with a photo of the mayor and the phrase “Sorry for partying.” The photo was originally taken by Kienitz, a journalist and conflict photographer, and used without permission. Kienitz sued Sconnie Nation for copyright infringement.

Sconnie Nation asserted fair use, and the district court agreed, granting summary judgment in favor of the defendant.

On appeal, the Seventh Circuit affirmed the lower court’s judgment but criticized its reasoning. Specifically, it took aim at the court’s reliance on the “transformative use” test, saying, “That’s not one of the statutory factors, though the Supreme Court mentioned it in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music.” It observed that the Second Circuit has embraced this test, most recently in its decision in Cariou v. Prince, where it “concluded that ‘transformative use’ is enough to bring a modified copy within the scope of §107.” Writing for the Seventh Circuit, Judge Easterbrook said,

We’re skeptical of Cariou‘s approach, because asking exclusively whether something is “transformative” not only replaces the list in §107 but also could override 17 U.S.C. §106(2), which protects derivative works. To say that a new use transforms the work is precisely to say that it is derivative and thus, one might suppose, protected under §106(2). Cariou and its predecessors in the Second Circuit do not explain how every “transformative use” can be “fair use” without extinguishing the author’s rights under §106(2).

The court nevertheless found the use fair, saying the t-shirts have not “reduced the demand for the original work.”

While Cariou’s approach to transformative use has been criticized before, Kienitz represents the first Circuit Court decision to do so.

Recall, Cariou involved the unauthorized appropriation of photographs of working-class photographer Patrick Cariou by celebrity artist Richard Prince. The Second Circuit held that 25 of Prince’s paintings were fair use, despite “Prince’s deposition testimony that he ‘do [es]n’t really have a message,’ that he was not ‘trying to create anything with a new meaning or a new message,’ and that he ‘do[es]n’t have any … interest in [Cariou’s] original intent.'” The court said that “The law imposes no requirement that a work comment on the original or its author in order to be considered transformative, and a secondary work may constitute a fair use even if it serves some purpose other than those (criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research) identified in the preamble to the statute.” The Supreme Court subsequently denied to review the Cariou decision.

I think Cariou was wrongly decided. But whether or not Kienitz represents a good vehicle for Supreme Court review, I think the occasion does provide a good place to reiterate the importance of necessity to fair use.

Judge Easterbrook raises this point, though it is ultimately of no help to Kienitz. Easterbrook observes:

[D]efendants did not need to use the copyrighted work. They wanted to mock the Mayor, not to comment on Kienitz’s skills as a photographer or his artistry in producing this particular photograph. There’s no good reason why defendants should be allowed to appropriate someone else’s copyrighted efforts as the starting point in their lampoon, when so many non-copyrighted alternatives (including snapshots they could have taken themselves) were available. The fair-use privilege under §107 is not designed to protect lazy appropriators. Its goal instead is to facilitate a class of uses that would not be possible if users always had to negotiate with copyright proprietors. (Many copyright owners would block all parodies, for example, and the administrative costs of finding and obtaining consent from copyright holders would frustrate many academic uses.)

Fair Use and Necessity

I’m not the first to describe fair use in terms of necessity. Alan Latman, going all the way back to his seminal 1958 study on fair use as part of the Copyright Law Revision process leading to the current Act, wrote:

Practical necessity is at times the rationale of fair use. Thus article 10 of the law of Argentina requires that an excerpt be “indispensable” to the purpose of the later work. The modus operandi of certain fields requires that the rights of each author yield to a step-by-Âstep progress. This consideration is often linked to the constitutional support for fair use as an indispensable tool in the promotion of “science.” Practical necessity and constitutional desirability are strongest in the area of scholarly works.

Similarly, in reviews of a work, a certain amount of reconstruction is often necessary; and in burlesque, the user must be permitted to accomplish the “recalling or conjuring up of the original.” Of more questionable necessity is the use of an earlier work in the preparation of a compilation. However, extensive use of earlier works as guides and checks appears to be common in this type of work which, although perhaps not achieving the intellectual aims inherent in the constitutional objective of copyright, does produce useful publications.

More recently, David Fagundes ruminates on the idea in a 2011 post, South Park & a Necessity Theory of Fair Use’s Parody/Satire Distinction:

Parody/satire may not track well onto the idea of transformativeness, but I do think it tracks well onto the idea of necessity. Necessity is a familiar defense to property torts. In the context of trespass, for example, emergency can entitle yachters stranded on a stormy lake to tie up at a stranger’s dock without permission, on the theory that avoiding the loss of their lives is more important than respecting the owner’s negative liberty (remember Ploof v. Putnam?).

And there are others who have looked at the idea of necessity in fair use, either favorably or critically.

Fair Use Justifications

Necessity derives from the justifications for fair use.

The earliest justification for fair use is grounded in the goals of copyright law itself. That is, “that a certain degree of latitude for the users of copyrighted works is indispensable for the ‘Progress of Science and useful Arts.'”

In one of the earliest law review articles on fair use, Judge Yankwich concludes:

[T]he earnest scholar and student, be he reviewer, critic or scientist in the same field, should have reasonable access to the work of others, lest we put—in the words of Lord Ellenborough—”manacles upon science.” On the whole, the law of “fair use,” as evolved by the courts, is a wise synthesis of conflicting rights which, while safeguarding the author, avoids injury to the progress of ideas which would flow from an undue “manacling” of others in the reasonable use of copyrighted material.

More recently, fair use has also been justified on free speech grounds. The Supreme Court has said on several occasions that fair use is one of copyright’s “built-in First Amendment accommodations”; it, along with doctrines like the idea-expression dichotomy, is “generally adequate” to address “First Amendment concerns.” In Eldred v. Ashcroft, the Court said fair use “allows the public to use not only facts and ideas contained in a copyrighted work, but also expression itself in certain circumstances.” When the expression itself is essential to a further purpose, such as news reporting or commentary, then fair use may allow copying. When it’s not essential, fair use should not apply, as the Supreme Court said in Harper & Row v. Nation Enterprises, where it held the unauthorized, verbatim copying of 300 words from an unpublished manuscript was not fair use:

Nor do respondents assert any actual necessity for circumventing the copyright scheme with respect to the types of works and users at issue here. Where an author and publisher have invested extensive resources in creating an original work and are poised to release it to the public, no legitimate aim is served by pre-empting the right of first publication. The fact that the words the author has chosen to clothe his narrative may of themselves be “newsworthy” is not an independent justification for unauthorized copying of the author’s expression prior to publication. To paraphrase another recent Second Circuit decision:

“[Respondent] possessed an unfettered right to use any factual information revealed in [the memoirs] for the purpose of enlightening its audience, but it can claim no need to ‘bodily appropriate’ [Mr. Ford’s] ‘expression’ of that information by utilizing portions of the actual [manuscript]. The public interest in the free flow of information is assured by the law’s refusal to recognize a valid copyright in facts. The fair use doctrine is not a license for corporate theft, empowering a court to ignore a copyright whenever it determines the underlying work contains material of possible public importance.” [Emphasis added.]

Taken together, these justifications suggest that throughout the history of fair use, there has been this idea that some overriding purpose is required to privilege a use that would otherwise be infringing. And the use of the original work must be necessary to the new work.

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose

This is precisely what the Supreme Court held in Campbell v. Acuff-Rose. In Campbell, the publishers of “Oh Pretty Woman,” written and recorded by Roy Orbison and William Dees, sued 2 Live Crew after it released “Pretty Woman,” a take-off on the Orbison classic that incorporated numerous elements from the song, including the famous bass riff, and added ribald rap lyrics. The district court had found the 2 Live Crew song to be a parody of the Orbison song, and the case made it to the Supreme Court on the issue of fair use.

This was the first time the Court would weigh in on whether parody may be fair use. It held that it could, saying, “Like less ostensibly humorous forms of criticism, it can provide social benefit, by shedding light on an earlier work, and, in the process, creating a new one.” In doing so, it drew a sharp distinction between parody and satire, defining the former as a work that comments on an existing work through mimicry while the latter copies for a non-related purpose.

For the purposes of copyright law, the nub of the definitions, and the heart of any parodist’s claim to quote from existing material, is the use of some elements of a prior author’s composition to create a new one that, at least in part, comments on that author’s works. If, on the contrary, the commentary has no critical bearing on the substance or style of the original composition, which the alleged infringer merely uses to get attention or to avoid the drudgery in working up something fresh, the claim to fairness in borrowing from another’s work diminishes accordingly (if it does not vanish), and other factors, like the extent of its commerciality, loom larger.

The Court went on to point out that this distinction hinges on necessity.

Parody needs to mimic an original to make its point, and so has some claim to use the creation of its victim’s (or collective victims’) imagination, whereas satire can stand on its own two feet and so requires justification for the very act of borrowing. [Emphasis added.]

The necessity requirement makes sense in light of the underlying justifications of fair use. If copying of expression is necessary for some speech purpose, fair use may excuse it so that copyright protection does not overextend and impinge on free speech interests.

When, however, copying expression is not necessary to a new work, there is no free speech issue, since the copyright owner cannot prevent others from communicating the facts and ideas conveyed by her work.

This distinction is illustrated in the Ninth Circuit’s 2012 Monge v. Maya Magazines decision. Maya, a gossip magazine, had published photos taken of a clandestine wedding of a young pop singer, one who maintained being single as part of her image. Maya argued fair use, characterizing the publication as news reporting and claiming, in part, that its “publication transformed the photos from their original purpose—images of a wedding night—into newsworthy evidence of a clandestine marriage.” It relied on the First Circuit’s decision in Nuñez v. Caribbean Int’l News Corp. as support.

In Nuñez, a newspaper had reprinted, without authorization, risqué photographs that had surfaced of a Miss Universe winner. The discovery of the photographs had sparked an inquiry into whether the model was fit to retain the Miss Universe title. The court disagreed that Nuñez supported Maya’s fair use argument.

Although Nuñez also involved news reporting, the similarities end there. The controversy there was whether the salacious photos themselves were befitting a “Miss Universe Puerto Rico,” and whether she should retain her title. In contrast, the controversy here has little to do with photos; instead, the photos here depict the couple’s clandestine wedding. The photos were not even necessary to prove that controverted fact—the marriage certificate, which is a matter of public record, may have sufficed to inform the public that the couple kept their marriage a secret for two years. [Emphasis added.]

Similarly, some use of expression may be necessary for commentary, criticism, quotation, or parody—all purposes that further the underlying goal of copyright in advancing art, science, and knowledge. Here, it bears repeating that, as a general rule, the protection of copyright will serve the purposes of copyright. When the original work is fungible to the new work—when there are alternative sources of raw materials for the second creator to draw upon—then the creation of the new work is not blocked. The second creator can “work[] up something fresh”, turn to the public domain for material, or find a work with more favorable licensing terms. Copyright’s purpose is to create a commercial market for creative works, and these outcomes are consistent with a functioning marketplace. When fair use privileges uses of original works that are not necessary to the creation of new works, it undermines this market, and, consequently, undermines copyright.

Toward a Fair Use Standard

Focusing on the necessity of the original work to the new use also puts the other factors into sharper focus. Take, for example, the third factor, which looks at “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole.” If there is no connection between the original and new works, what standard guides courts in weighing this factor? How much use of a work is “fair” when it is not necessary to a new work? In this case, the inquiry becomes redundant with a substantial similarity analysis.

But when there is a connection between new and original works, courts have a standard to guide analysis of the third factor. Campbell provides a clear application of this principle in the context of parody.

Parody’s humor, or in any event its comment, necessarily springs from recognizable allusion to its object through distorted imitation. Its art lies in the tension between a known original and its parodic twin. When parody takes aim at a particular original work, the parody must be able to “conjure up” at least enough of that original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable. What makes for this recognition is quotation of the original’s most distinctive or memorable features, which the parodist can be sure the audience will know. Once enough has been taken to assure identification, how much more is reasonable will depend, say, on the extent to which the song’s overriding purpose and character is to parody the original or, in contrast, the likelihood that the parody may serve as a market substitute for the original. But using some characteristic features cannot be avoided.

In fact, it’s often forgotten that the Supreme Court did not hold that 2 Live Crew’s use was fair. It instead remanded to the district court to determine fair use, and in its discussion, it continues to be clear that a necessity requirement underlies fair use.

Suffice it to say here that, as to the lyrics, we think the Court of Appeals correctly suggested that “no more was taken than necessary,” but just for that reason, we fail to see how the copying can be excessive in relation to its parodic purpose, even if the portion taken is the original’s “heart.” As to the music, we express no opinion whether repetition of the bass riff is excessive copying, and we remand to permit evaluation of the amount taken, in light of the song’s parodic purpose and character, its transformative elements, and considerations of the potential for market substitution sketched more fully below.

The two parties settled following the Supreme Court decision, agreeing to a license.

In recent decades, fair use has categorically expanded to include the copying of entire works for new purposes rather than new works—for example, time-shifting, mass digitization, or image search. In these situations, necessity may not play the same role, if it plays one at all. But in its historical application—as a privilege for the incorporation of expression from an existing work into a new work—courts should look at necessity. Whether necessity is an essential element of fair use is a separate question, but at the very least, it should play a key role in any fair use inquiry to ensure that the doctrine remains consistent with copyright’s ultimate goals.