Below is the full text of the Sixth Annual Donald C. Brace Memorial Lecture presented by former U.S. Register of Copyrights Barbara A. Ringer on March 26, 1976, titled “Copyright in the 1980’s.” Copyright in the lecture was expressly disclaimed by the author.

I wanted to make the lecture available here for two reasons.

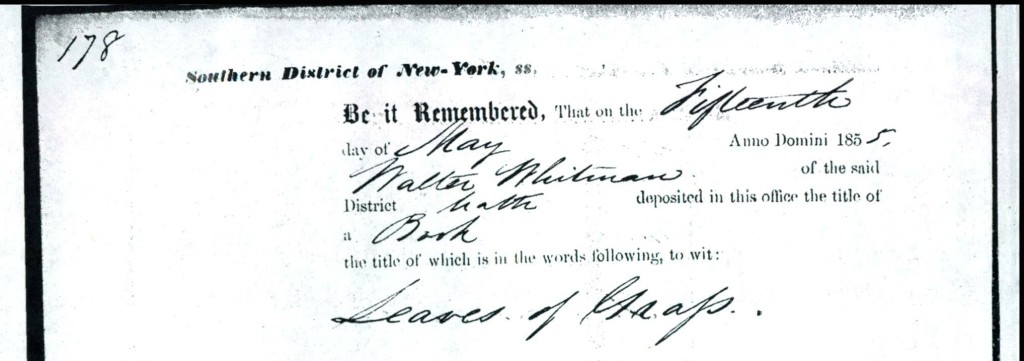

First, I think Ringer’s remarks are both historically compelling and still relevant today. Less than a month before Ringer delivered her lecture, the Senate passed S. 22 by a vote of 97-0—a bill that would completely rewrite U.S. copyright law, both in form and in substance. But by this point, Congress was 15 years into the effort to revise copyright law (over 20 years if you start counting when Congress directed the Copyright Office to produce a series of copyright law revision studies that would serve as the foundations for the effort). Several times, this effort came close to being derailed over contentious issues. So it’s understandable that Ringer couches her remarks with uncertainty over the fate of the revision effort, even in the face of a unanimous Senate vote.

But Congress would finally succeed this time. Two weeks after Ringer’s remarks, given in front of the Copyright Society of New York, the House Judiciary Subcommittee on Courts, Civil Liberties, and the Administration of Justice would begin markup of S.22, leading to President Gerald Ford signing the bill into law October 19, 1976.

The difference between the new and old laws cannot be overstated. But the influence of Ringer on the revised act is often understated. Ringer served in the U.S. Copyright Office during the entire two decade revision effort, the last several years as Register of Copyrights (securing that role only after prevailing in federal court on sex and race discrimination claims after being passed over for a less-qualified man). Anecdotally, Ringer has been credited with drafting at least “75%” of the Act’s text, an enormous undertaking that involved balancing the equities of numerous, competing interests; rationalizing complex and technical language over a sprawling, comprehensive Act; and keeping a keen eye toward an unknown future to craft a law capable of maintaining its coherence during rapid technological changes.

So her observations about where copyright law will go in the decade following the new copyright act are especially instructive, born out of her experience shepherding the revision effort. Her lecture touches upon themes Ringer had spoken about previously (such as in her 1974 article, The Demonology of Copyright)—the fragile state of individual authors, the degrading effects of technological progress, and both the promise and shortcomings of the current revision effort for authors and society.

My second motivation for making the lecture available here is because, despite its public domain status, the only freely accessible version I could find online is a low-quality scan made available through ERIC, which is difficult to read in parts.1https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED126906.pdf. I have done my best to transcribe the text accurately and apologize for any errors. I have also added footnotes (judiciously, I hope) to provide additional context where appropriate or helpful.

Copyright in the 1980’s

By Barbara Ringer*

*Register of Copyrights. The views of the author are personal and are not intended to reflect any official positions of the Copyright Office or of the Library of Congress. No copyright is claimed in this lecture.

When Paul Gitlin2Among other things, Gitlin, a pioneering literary agent, co-wrote a 1963 Practicing Law Institute monograph titled “Copyrights” with Ringer. called to invite me to deliver the Sixth Donald C. Brace Memorial Lecture, he did me more honor than he knew. Donald Clifford Brace was a truly outstanding publisher, who brought to the American public the works of some of the greatest English authors of the Twentieth Century. Among them is the single writer whose works and voice and life have spoken to me more directly than that of any other: George Orwell.

In 1946 Orwell wrote to his agent, Leonard Moore:

You mentioned in your last letter something about giving Harcourt Brace an option on future books. It’s a bit premature as I have no book in preparation yet, but I should think Harcourt Brace would be the people to tie up with, as they had the courage to publish Animal Farm. But of course they may well be put off the idea if the book flops in the USA, as it well may. I am not sure whether one can count on the American public grasping what it is about. You may remember that [a certain publisher] had been asking me for some years for a manuscript, but when I sent the MS of AF in 1944 they returned it, saying shortly that “it was impossible to sell animal stories in the USA.” . . . . So I suppose it might be worth indicating on the dust-jacket of the American edition what the book is about. However, Harcourt Brace would be the best judges of that.

Harcourt Brace did, in fact, go on to publish Orwell’s next work, one whose literary and historical significance, and whose ultimate social influence, cannot be exaggerated. The title of Orwell’s work, “1984” has become a symbol and, I fear, a political slogan of exactly the kind he was attacking in the book. The popularity of the title as a catch phrase has obscured and distorted the meaning of the work itself. Orwell, who was dying when the novel was published in 1949, cast his story in terms of the utmost pessimism, but his intention was the opposite of despair. “1984” is a kind of hymn to what Erich Fromm has called the very roots of Occidental culture: the spirit of humanism and dignity. Most of all it is a warning that the values on which our culture is based—of individualism, idealism, and free expression—are in the most immediate possible danger, not from any particular ideology or political system, but simply from the juggernaut of technology. Orwell was powerfully and desperately trying to warn us of the new barbarism just around the corner, of “the new form of managerial industrialism in which,” to quote Fromm’s trenchant essay, “man builds machines which act like men and develops men who act like machines”— of “an era of dehumanization and complete alienation, in which men are transformed into things and become appendices to the process of production and consumption.”

For publishing this book, and for publishing George Orwell at all, Donald Brace deserves to be thanked and honored. The message Orwell was seeking to convey affected the lives and actions of some members of my generation very profoundly. And yet today, less than eight years from the date Orwell chose as his particular doomsday—when everything he predicted is coming true, and not just in other countries—we accept these horrors as inevitable or even acceptable, and spend most of our time looking for personal anodynes.

When he first called to ask me about making this lecture, Paul Gitlin had just seen a piece I wrote for the Centennial Issue of the Library Journal titled “Copyright and the Future Condition of Authorship.” He said he found the tone of my essay pessimistic, and he rather implied that I might do well to make this lecture a little more up-beat. As I told him, my own feeling is not one of despair, and I certainly have no wish to plunge anyone into a blue funk over what is happening to copyright and the condition of authorship. But in copyright, which is the particular field I am called upon to plow, I do believe that people should be made to recognize the dangers and to realize that there is still a chance to do something toward averting them.

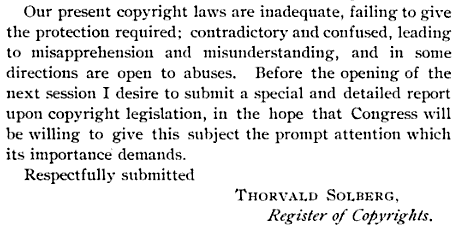

I am making these remarks at a time that may prove to be a major turning point in the history of American copyright law. In February the bill for general revision of the copyright law, which has been pending in Congress for nearly 12 years, passed the Senate unanimously by a vote of 97 to nothing. Progress in the House of Representatives has been slow, and I see enormous difficulties in the months ahead, but I still believe it is safe to predict enactment of the bill this year. If I am wrong, if the efforts to reform the present copyright statute of 1909 have to continue into the 1980’s in the face of on-rushing technological change, I am afraid the picture I am painting will be much darker and bleaker than I anticipate.

I prefer to look on the brighter side. I base my analysis of copyright in the 1980’s on the assumption that S. 22 of the 94th Congress will be in effect before the start of that decade, and that the impact of its changes will already have been felt. These changes will certainly lay the basis for the conditions of authorship and the dissemination of authors’ works during the last quarter of this century.

When I began to frame the outline of this lecture I first thought I would take the specific provisions of S. 22 and project them into the 1980’s, in an attempt to analyze how they should work out in practice. It did not take me long to realize that this approach would be both too difficult and too easy: too difficult because of the amount of complex detail and imponderabilia involved, and too easy because it is always simpler to analyze the trees and ignore the forest and the surrounding terrain. Instead, and with considerable misgivings, I will try to take the trends I see working upon and through the domestic revision bill—and in international copyright—and to project what may emerge from them in the next decade. I will try to deal with these trends under four general headings:

1) The nature of copyrightable works and the methods of their dissemination;

2) The nature of rights in copyrightable works;

3) The situation of individual authors; and

4) The role of the state in copyright and authorship.

The nature of copyrightable works and the methods of their dissemination

I believe, with Orwell, that mankind is changing the world through technology and that technology in its turn is changing mankind into technological beings. Where does this leave the creative individual and his ability to present his ideas and creations to others?

It seems almost superfluous to observe that the technological revolution in communications is a pivotal event in the history of mankind and that its full impact has not yet been felt. Among the plethora of electronic marvels now arrayed for our use, there are those that are merely transitory toys and gadgets, but there are others that seem to some people to have god-like qualities. It is certain that, amid all the electronics and advertising, the quality of human life is changing, and that the real impact of the change has not yet been felt.

Anyone who sits down and thinks about what has happened to mass communications since 1909 can come up with quite a list. Silent and later sound motion pictures; radio and later television and still later cable and pay-television; computers and their ability to assimilate, generate, and manipulate limitless amounts of information; satellites and their potential for reaching and linking everyone on earth; sound recordings and later audio and video tape recordings; photocopying and microreprography; and automation in the composition and reproduction of printed matter. This certainly does not exhaust the list, and many of these developments combine and interact, providing nationwide and worldwide networks for quick or instantaneous dissemination of what passes for information and entertainment. And there is evidently no end to this process: a satellite is already making direct transmissions into individual receiving sets in India;3I believe this is a reference to the Satellite Instructional Television Experiment. holography is beginning to lose its mystery; and lasers are being used for all sorts of things: for data storage, for communications channels into homes, and as part of commercial video disk players soon to enter the consumer marketplace.

On the face of it, all this opens tremendous new channels for creative endeavor and new ways of reaching huge audiences of readers, and viewers, and listeners, and information seekers. Like the invention of movable type and of painting techniques and musical instruments during the Renaissance, technology is bringing a whole new breed of creators into the communications arts. It is also allowing traditional creators to fix their works permanently and literally to get them into the hands of anyone who wishes to see or hear them. The 90’s should see some startling developments in one-way, two-way, and unlimited wireless communications.

Despite the cynicism and alienation that we see everywhere today, most people still welcome each technological “advance” as some sort of miracle and rush to buy and use it for purposes that, if pressed, they might have trouble articulating. Yet, unless I misjudge the signs, there is a growing realization that all this machinery has done less than nothing to improve human life, and the more voracious our craving for technological advance, the more individual people suffer. Instead of fostering perfection in the arts and the creation of masterpieces, the communications revolution has already maimed a number of traditional forms of expression and is destroying our standards, our ability, and our desire to judge our own culture.

I remember someone predicting a few years ago that, if the present trends continue, by the end of the century we will have a great many more birds than we have now, but that they will almost all be either pigeons and starlings. I have the same feeling about the effect of technology on copyright: a great many more works are going to be copyrighted in 1986 than in 1976, but their intrinsic value will continue to decline.

I believe that the courts and the Congress will continue to expand the subject matter protected by copyright and to cover the new uses of copyrighted works made possible by the expanding technology. But if the effect of this limitless expansion is to destroy incentives to truly creative work, to substitute remuneration for inspiration, and to make great creative works compete unequally with vastly increased quantities of trash and propaganda, we will have lost much more than we have gained.

The nature of rights in copyrightable works

Throughout the whole range of national and international copyright regimes since 1950, a single concept insistently recurs: it is usually called compulsory licensing, although in its various guises it may be referred to as “obligatory,” “statutory,” “legal” or “agreed” licensing. Characteristically, it is offered as a compromise to copyright controversies in two situations: where technology has created new uses for which the author’s exclusive rights have not been clearly established, and where technology has made old licensing methods for established rights ponderous or inefficient.

Under a typical compulsory licensing scheme, the author loses the right to control the use of his work, and cannot grant anyone an exclusive license for a certain specified purpose. Instead, his work is lumped with thousands or millions of other works, and the author also becomes a unit in a large collective system under which blanket royalties are received and distributed. The government is involved in operating the system, and the individuality of both authors and works tends to be lost. Authors may be paid well for the use of their works, but their participation in the system is, by definition, compulsory rather than voluntary.

It may come as a shock to realize that S. 22, as it now stands, contains four full-fledged compulsory licenses involving rate-making by a Government tribunal. A separate piece of legislation, which will be pushed very hard in the House, raises the possibility of a fifth, and others may emerge before the bill is finally enacted. As we go into the 1980’s, copyright is becoming less the exclusive right of the author and more a system under which the author is insured some remuneration but is deprived of control over the use to which his words are put.

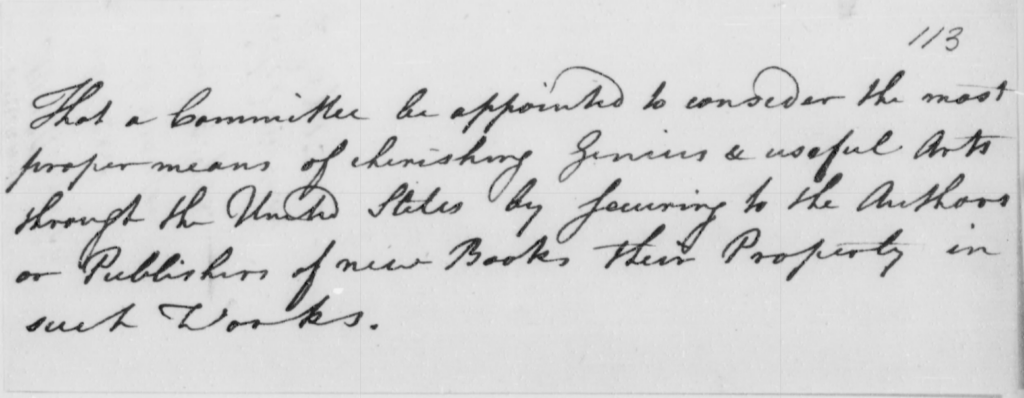

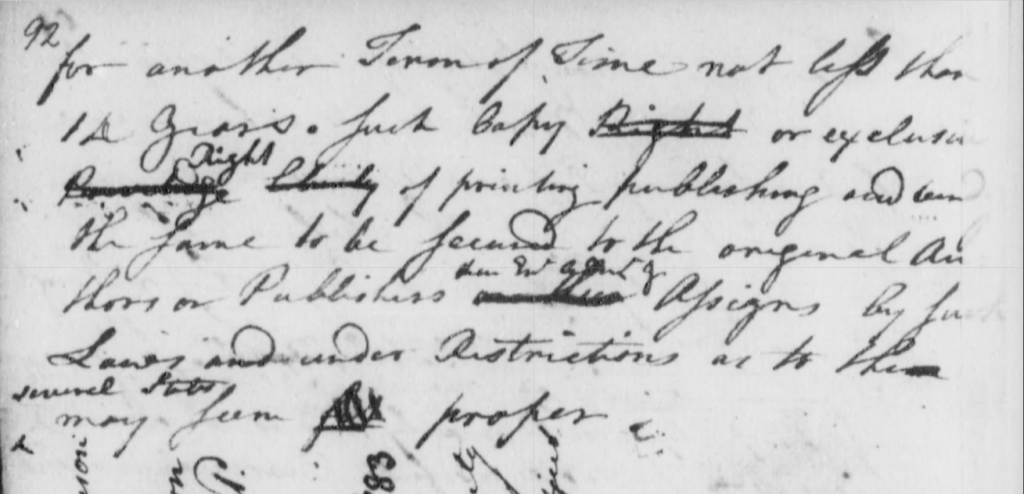

In 1908, Congress was confronted with a peculiar dilemma of either giving exclusive rights to musical copyright owners, and thereby allowing the creation of what they referred to as a giant music trust, or of withholding these rights and thereby causing a great injustice to creators. Congress devised what, to my knowledge—and I have never been challenged on this statement—is the first compulsory license in history, section 1(e) of the present law. There may well have been intellectual antecedents to this under specific court decisions or in private, blanket licensing arrangements; but, as far as statutory, across-the-board, arrangements are concerned, I believe that the copyright royalty for sound recordings was the first compulsory license in the world.

It was copied almost immediately in the copyright statutes of other countries, in the same context of mechanical royalties for recording music. The situation as it evolved in the statute meant that a two-cent limit was imposed on the amount of royalties a copyright owner could get for having a song recorded. Once the owner of the copyright in a musical composition licensed his work for recording, everyone else had a right to make a recording by paying two cents per song per record. This is still the law, all these years later, and it is getting on towards 70 years now.

It would seem, on the basis of a great deal of experience, that this compulsory license is as firmly rooted in our copyright law as anything can be. I suspect that, by the time S. 22 is enacted into law, the two-cent rate will have been raised somewhat, but it is probably too late to raise any philosophical questions about compulsory licensing in this context. Indeed, the trend is exactly the reverse: to expand the concept of compulsory licensing into every new form of use of copyrighted works created by changes in communications technology. This seems certain to be true in the case of jukebox performances and cable television transmissions.

The cable issue, in particular, has been the reef on which copyright law revision foundered for seven years. In 1967, the House Subcommittee, confronted by this new and highly controversial issue, tried as forthrightly as possible to solve the problem through a rather simple form of compulsory license, and without imposing the heavy hand of government regulation. This effort was doomed to failure. The reason was that no one knew what the liability of cable systems was under the law, as construed in 1967. They do now: the Supreme Court has twice held in favor of cable and against exclusive rights under the copyright statute.

Cable became a roaring issue in 1967 and, as a result, when the House passed the bill, the whole cable provision was simply wiped away and the problem was passed to the Senate.

The Senate, in turn, evolved a whole new concept of protection for cable uses of copyrighted works which rested upon a compulsory license and added a new and very significant institution, a copyright royalty tribunal. This new device, which was inevitable when the House approach of 1967 failed, would create a government-associated body empowered to make decisions with respect to the practical running of the compulsory licensing system. Rates would be subject to review by this tribunal and decisions would be made with respect to the distribution of fees.

All three of these compulsory licenses—the so-called mechanical royalty, the jukebox compulsory license, and the compulsory license for cable television—seem certain to be enacted in some form. All three are very deeply rooted in the bill, and they are all related, in one way or another, to a copyright royalty tribunal that would be involved in rate-making and in the distribution of fees.

In 1969, the Senate Subcommittee added a fourth compulsory license for the performance of sound recordings. This turned out to be one of the most controversial provisions in the bill. It was knocked out in the Senate in September of 1974 and has not yet been reintroduced. Interestingly, for a generation or more the organized musicians turned their back on copyright protection and sought to protect their interests through collective bargaining and a controversial trust-fund device. Now, in a complete turnabout, the whole AFL-CIO has joined with the record industry in a concerted effort to enact a copyright law establishing a royalty for the performance of sound recordings in radio and other media. Of course, this is being fought vigorously by the broadcasting industry, and the fight will probably go right down to the House floor, promising a dramatic confrontation.

I am supporting this proposal in principle because I think it is unfair that individual performers have rarely received any of the benefits from the great technological developments that have, to a large extent, actually wiped out their profession. Fairness indicates that it is wrong that they not get paid for performances of their works, and I believe that sooner or later this right will be recognized under some form of compulsory licensing.4As of the time of publishing, performers in the US do not have a general public performance right for their sound recordings. A bill introduced in the 117th Congress, the American Music Fairness Act (H.R. 4130), would have created a right of performance publicly by means of an audio transmission and is the latest in a long line of legislative attempts to remedy the issue raised by Ringer above. Congress did grant an exclusive right for public performance by digital audio transmissions in 1995, and, in line with Ringer’s prediction, created a statutory license covering certain types of transmissions.

When this provision was in the bill the public broadcasters said, “Well, for heaven’s sake, if all these commercial interests are going to get something like this compulsory license, why shouldn’t we? We public broadcasters are not paying any copyright royalties now, but we recognize that we should. But, even if we have to pay something, we cannot put ourselves in the position of having to get individual clearances for all the music we play, all the graphic works that we show on the screen, and all of the literary works that we read over public radio and on the tube.”

They took their problems to Senator Mathias and apparently made a persuasive case, because we now have a new Section 118 in the bill as it passed the Senate. It would create a rather amorphous compulsory license for the public broadcasting of musical compositions, nondramatic literary works, and pictorial, graphic and sculptural works. It would leave to the proposed royalty tribunal the problem of setting the terms, rates, and the entire mechanism for running the compulsory license.

I am opposed to this provision, and particularly its impact on the whole range of nondramatic literary works.5The Copyright Office as a whole shared this view of the proposed amendment. The Office published a Public Broadcasting Report in May 1980 as provided by the 1976 Copyright Act that details the background and legislative history of the proposal along with voluntary licensing agreements for the use of nondramatic literary works by public broadcasters in the wake of the 76 Act. At the same time, I am aware of the vast political power of public broadcasters, and I think the chances of facing compulsory licensing in this area in the 1980’s are better than ever.

What we have seen demonstrated in the evolution of these five compulsory licensing schemes, and others that seem to be right around the corner, is a kind of inexorable historical process.

- First you have a copyright law that was written at a particular point in the development of communications technology, and without much foresight.

- Then you have technological developments, which create whole new areas for the creation and use of copyrighted works.

- Business investments are made and industries begin to develop.

- The law is ambiguous in allocating rights and liabilities, so no one pays any royalties.

- A point is reached where the courts simply stop expanding the copyright law and say that only Congress can solve the problem by legislation.

- You go to Congress, but you find that you have hundreds of special interests lobbying for or against the expansion of rights, and the legislative task is horrendous.

- So Congress, looking for a compromise, turns to compulsory licensing. On its face, a compulsory licensing system looks fair to each side: the author and copyright owner get paid, but the user, who has made a strong argument that what he is doing represents the public interest, cannot be prevented from using the work.

We have reached the point where any new rights under the copyright law apparently cannot be exclusive rights. If a new technological development makes new forms of exploitation possible, compulsory licensing seems to offer the only solution. This is happening in the United States and it is happening just as much internationally. Compulsory licensing systems represent key provisions in the 1971 revisions of both the Berne and Universal Copyright Conventions, and in recent copyright laws in other countries.

Before the present program for general revision of the copyright law began in 1955, the United States had endeavored successfully to develop an international convention which would provide multilateral copyright relations between Western Hemisphere countries and the European countries members of the Berne Convention. The result was the Universal Copyright Convention, which was signed in Geneva in 1952 and came into effect in 1955.

In its origins the Universal Copyright Convention was considered a low-level transitional treaty which would dry up and blow away as more and more of its members accepted the principles of the Berne Convention. The confident assumption twenty-five years ago was not only that the level of protection reached at the Brussels revision of the Berne Convention in 1948 constituted the norm in international copyright, but that even its relatively high level of protection would continue to rise and expand.

These expectations, have proved false, for at least three interrelated reasons:

- First, the technological revolution in communications and the compulsory licensing demands that it has spawned in practically all countries.

- Second, the needs of developing countries. At crucial conferences in Stockholm in 1967 and Paris in 1971 the developing countries made a persuasive case for an international copyright system that gives them ready access to the materials they need to combat illiteracy, provide educational and scientific and technical information for their peoples at prices they can afford to pay. Whether the 1971 revisions of the two conventions have achieved this goal as a practical matter remains to be seen.

- The concessions made in the Paris revisions of both the UCC and Berne Convention, in a general sense, are an attempt to preserve the principles of copyright in the face of the needs of states with limited resources, confronted with difficult and pressing development choices in allocating their expenditures. In this light, the Paris revisions looked towards greater interdependence and cooperative trading relationships within the world copyright community. Whether this approach is realistic in an increasingly inflationary world economy is far from certain.

- Third, the impact of socialist legal thinking. The adherence by the USSR to the 1952 text of the UCC, effective on May 27, 1973, was a dramatic illustration of a trend already apparent in international copyright.

The situation of individual authors

All of these forces seem to be combining throughout the world to substitute compulsory licensing and various forms of state control for exclusive copyright control, and to substitute remuneration for voluntary licensing arrangements. Individual authors, standing alone, are helpless to protect themselves in a situation like this. Ironically, in order to preserve their own independence as authors, they will inevitably be forced to unite in collective bargaining organizations, and to allow their representatives to speak for them.

Authorship, by which I include all kinds of creative endeavor, is in an extraordinary state of flux. For some two hundred years, from the end of the patronage system in the late 17th Century to the emergence of the new technology in the beginning of the 20th Century, authors enjoyed something like a direct one-to-one relationship with their readers through their publishers. This relationship has ceased to exist entirely in some creative fields, and is fast disappearing in others. Authors are losing their ability to speak directly to readers, listeners and viewers, and must now deal with increasing hordes of middle-men who control the communications media or the access to them. In this situation it is quite possible to envision the mergence of societies in which there is little individual or independent authorship; most creative work would be done as part of collective endeavors, merged together anonymously, and whatever individual writing remains would be done under the patronage and control of the state.

Copyright is obviously caught up in a social tidal wave. In trying to preserve independent, free, authorship as a natural resource, one must be aware of the changes that are taking place and cautious about the methods adopted and deal with them. Some ideas that are put forward as solutions to practical problems of copyright clearance and access to information may turn out to be more destructive to our society than the problems they are supposed to solve.

I confess that at this point I come to the first of two dilemmas in my present thinking about the next 20 years—questions that I consider of immense importance but to which I can see no clear-cut answers. The first is what individual authors can do to protect themselves from this onslaught of technology. We have already reached a turning point in several areas, and are fast approaching it in others, where the individual creator simply cannot assure himself of fair remuneration for the use of his works unless he joins a collective organization of some sort. ASCAP and BMI are examples of one sort of collective organization in which authors pool their copyrights but maintain some degree of individual ownership and control over their use. The other most common type of organization is a trade union, which represents its members as employees and bargains for them on a collective basis.

There is, quite obviously, a loss of independence in both cases, and for some authors and for some types of work this may prove an intolerable sacrifice. But what are the alternatives? A continuing alliance with publishers or equivalent middle-men in which the individual author’s voice cannot be heard? Direct government control over licensing? Direct government patronage?

These are the questions that will inevitable have to be faced and answered in the 1980’s, and I find it astonishing that so far there is very little awareness or discussion of them. The discussion should be undertaken by the authors and creators themselves, not by lawyers or government types like me, and not by publishers or film producers or information industry representatives. But a movement toward clearinghouse arrangements and collective licensing has already started, and unless the implications and alternatives are carefully examined, patterns may become established that authors will soon find themselves powerless to change.

The role of the state in copyright and authorship

The most critical question arising from all of these trends involves the role that government will play in the operation of the copyright systems of the 1980’s. In the United States that role is clearly expanding. It seems inevitable that the government will shortly be involved in setting regulatory standards and royalty rates, in settling disputes over distribution of statutory royalties, and in establishing means by which individual authors organize for the payment of royalties. How far this process is allowed to go, and how irreversible it is allowed to become, will depend on decisions that must be taken in the immediate future.

My second dilemma thus involves the Copyright Office and what is to become of it. Recognizing what happens whenever bureaucratic nature is allowed to take its course, I feel that the office must resist the lure of embracing new regulatory powers over copyright licensing which could easily grow into government control over the conditions of authorship. Yet, I feel just as strongly that the Copyright Office cannot simply walk away from the problem, leaving it to other would-be government regulators or communicators or patrons to fill the vacuum. The decisions on this question, whatever they are, must be taken in full realization of the dangers facing independent authorship in the next decade, and in full determination to surmount them.

References

| ↑1 | https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED126906.pdf. |

|---|---|

| ↑2 | Among other things, Gitlin, a pioneering literary agent, co-wrote a 1963 Practicing Law Institute monograph titled “Copyrights” with Ringer. |

| ↑3 | I believe this is a reference to the Satellite Instructional Television Experiment. |

| ↑4 | As of the time of publishing, performers in the US do not have a general public performance right for their sound recordings. A bill introduced in the 117th Congress, the American Music Fairness Act (H.R. 4130), would have created a right of performance publicly by means of an audio transmission and is the latest in a long line of legislative attempts to remedy the issue raised by Ringer above. Congress did grant an exclusive right for public performance by digital audio transmissions in 1995, and, in line with Ringer’s prediction, created a statutory license covering certain types of transmissions. |

| ↑5 | The Copyright Office as a whole shared this view of the proposed amendment. The Office published a Public Broadcasting Report in May 1980 as provided by the 1976 Copyright Act that details the background and legislative history of the proposal along with voluntary licensing agreements for the use of nondramatic literary works by public broadcasters in the wake of the 76 Act. |